Dr Cameron Taylor (2009) read Linguistics and Italian at St John’s, and he now works as an AI Interactions Architect at Boost AI, where he improves human-robot interactions using his language knowledge and research into how people communicate. Read on to discover what lessons robots can learn from humans and how advances in automation might affect our future.

My experiences studying and working in the US, Italy, the UK and Norway have taught me that there is a lot more that unites us than divides us. The years I spent at St John’s were some of the most formative of my life, and I use the skills I learnt there daily in my job at Boost AI, a Norwegian conversational AI company that creates the most successful text- and voice-based virtual customer service agents in Scandinavia.

There are many lessons from human-human interactions that can apply to human-robot interactions. We often misunderstand each other in conversation (anyone in a relationship can relate), but there are universal repair-mechanisms found across languages for this.

For example, we interject ‘What?’ or ‘Huh?’ in conversation when there is an ambiguity or when there is a mechanical failure, such as water blocking the eardrum or an ambulance driving by mid-sentence.

When we think we caught only some of what was said, we’ll often offer it as a suggestion: ‘Did you say “skeleton”?’ Or if we only half-remember what someone said, we’ll ask them: ‘Sorry, did you say liver or salad?’

These conversational techniques may seem obvious to us, but robots need to be taught them to avoid frustrating their human interlocuters with a repeated ‘Sorry I didn’t catch that’.

Some programming developments, such as Automatic Semantic Understanding (ASU), reduce false positives by detecting different levels of uncertainty. The algorithm then responds with two best guesses, so if you are ordering a pizza and the bot didn’t understand what you said, rather than saying ‘Sorry I didn’t catch that’ it might say ‘Sorry, did you say mushrooms or onions?’

Conversational AI can adapt its tone and personality depending on how the user speaks to it and the type of question asked, but this depends on the training that goes into it, what systems the software integrates with and what the purpose of the bot is.

We built a bot for Helsinki University Hospital to help triage mental health patients, since the staff thought that young men suffering from depression and anxiety might be more willing to disclose their emotional problems to a bot than to a live nurse. Unsurprisingly, we programmed this to respond differently than a bot used to support insurance claims.

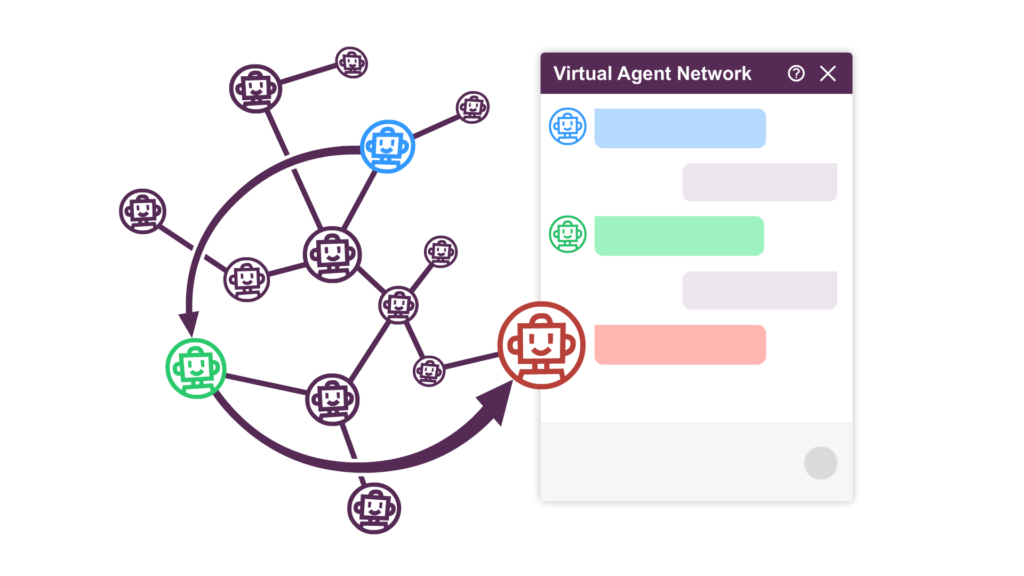

We have also developed the ability for bots to talk to each other and to transfer end users to the most relevant service. In Finland we deployed virtual agents for the Immigration Service, the Tax Administration, and the Patent and Company Registration Office.

We noticed that the Immigration Service bot was receiving lots of questions that were more appropriate for these other government agencies. Now if a person asks the Tax Administration bot a question related to visas, it will ask them if they would like to be transferred to the Immigration Service bot.

Exciting advances are being made in neuromorphic hardware, which aims to mimic the human brain. These computer chips will allow bots to take in, understand and respond to much more nuanced data, such as odours in the room. Because this hardware also consumes less power, we would be able to more easily create embodied bots, eg talking chairs and tables.

Once [computers] are able to accurately assess how we feel, they may also be able to manipulate how we feel

While technological advances in making computers more humanlike are incredible, there is a danger that this hardware will increase faster than our ability to understand ourselves and how our minds work. Computers are not yet able to detect emotions with accuracy beyond ‘calm’ and ‘excited’ (either of which could indicate joy or anger), but once they are able to accurately assess how we feel, they may also be able to manipulate how we feel. Clear benefits and ethical challenges arise from this. Technology will continue to help us tremendously, but if it gains too much power over our lives then we might become hostage to the agenda of sophisticated marketing teams.

With the pandemic driving more traffic online, we have noticed an enormous spike in usage of chatbots, especially from public agencies. We run a virtual agent called Frida for the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV), the government agency which is responsible for administering many of Norway’s key social benefit programmes (eg pensions, child support, unemployment benefits and employee sick leave). The director of NAV’s contact centre told us that since the beginning of the lockdown in Norway, if Frida hadn’t been there they would have needed an extra 220 full-time employees to handle all the enquiries.

One virtual agent can respond to thousands of people at once, and a well trained, well-designed, high-quality virtual agent answers about 80% of enquiries, with the remaining 20% needing to be escalated to a human.

At Boost AI we offer free training to anyone who wants to learn how to become an AI trainer, which is a person who builds and maintains a virtual agent. This creates new jobs, but it may not create equal opportunities to cover redundancies.

Automation will inevitably change the way we work, and we need to take the impact of automation on jobs seriously. Unless we want to drift into a future of greater economic inequality, this will require political engagement and fresh thinking around the relationship between income and work.

This year has been particularly tough. Like many others I have been unable to travel to visit family, and working from home has presented new opportunities and challenges. I have relied on a vipassana meditation practice, which reminds me that everything always changes.

I have also gained a few kilos, which will require some discipline this summer to shed! But working in the technology industry has been fascinating because the pandemic has accelerated progress exponentially in a way that I don’t think would have otherwise happened.

While studying at St John’s, Cameron met a Tibetan monk and arranged for the Dalai Lama to visit Cambridge. This laid the groundwork for Cameron setting up the Inspire Dialogue Foundation to facilitate intergenerational and interdisciplinary conversations on global issues.

Written by

Gates Cambridge Scholar and Executive Director of the Inspire Dialogue Foundation, Cameron has studied and lived in the US, Italy, the UK and Norway. He now works as an AI Interactions Architect at Boost AI, improving robot-human chatbot interactions.