Sam Davies (1993) graduated from Engineering at St John’s and immediately began her career as a yachtswoman with her first around-the-world crewed race for the Jules Verne Trophy in 1994. Since then she has competed in more than 25 transatlantic races, including three Vendée Globes, in which contestants aim to sail around the world solo, non-stop and without assistance. Early in February, three months after the start of her third Vendée Globe and while she was still sailing the course, Sam answered my questions from her constantly moving boat.

Where did your passion for sailing come from?

It’s in my genes, from both sides of my family. My paternal grandfather, who is one of my heroes, became a submarine commander aged 26 and survived the war. My maternal grandfather had a boatyard and raced powerboats offshore.

My parents love sailing, so I learnt to handle a boat and enjoy life on the water from an early age. When I was growing up, sailing was reserved for weekends and holidays. It was purely a family fun activity, and it wasn’t until I was in my late-teens that I began racing with friends at the local yacht club.

During this race are you mostly reacting to situations or planning next steps?

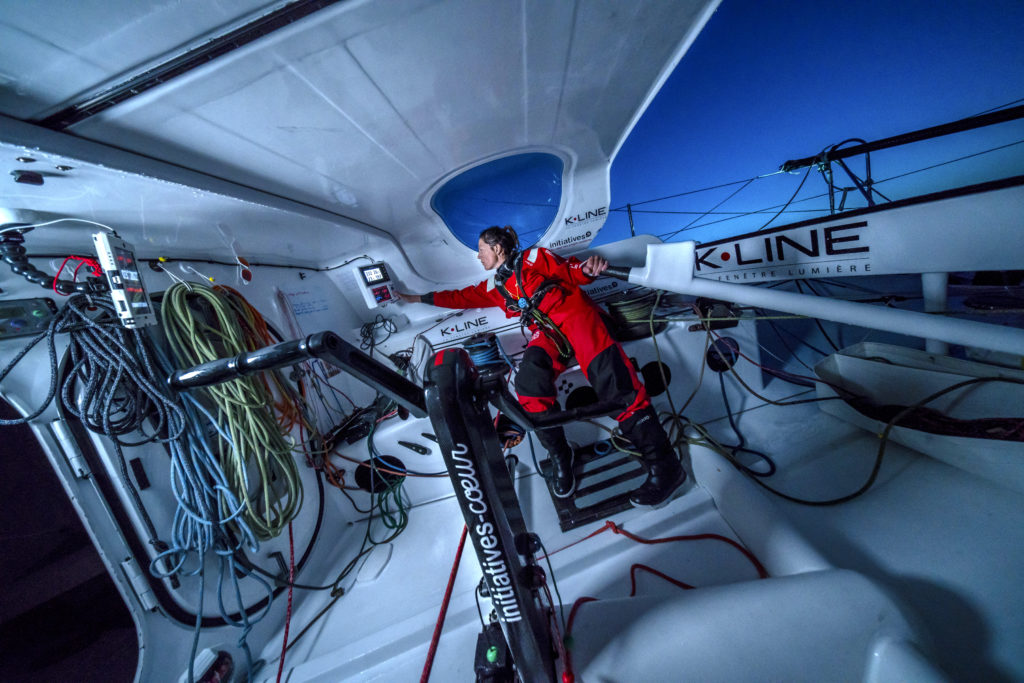

The objective is to keep the boat sailing at 100% of its potential all the time, so there’s lots of sail-changing and sail-trimming and working the boat to ensure it is travelling at the right angles compared to the seascape. I also need to react to the boat itself, tending to and fixing anything that is broken or weak.

I do have to plan my own route, though, and I make all the tactical and meteorological decisions myself. Major weather updates arrive at 5am and 5pm, so that’s when I sit down to work on my computer, looking at strategy and weather forecasting.

Photography: Eloi Stichelbaut

Photography: Yann Riou

Photography: polaRYSE / Initiatives Coeur

Photography: Anne Beaugé

How do you keep yourself motivated, sane and healthy?

I’ve already sailed around the world several times, and I’ve been mentally preparing for this for 3–4 years. Since it’s my choice, the isolation I’m facing is different from that imposed on people by COVID-19.

In a race you have to push yourself so hard that you live in an extreme state of exhaustion, and it’s essential to keep well-rested, eat enough food and maintain good hygiene. That can be difficult on a moving boat with no bathroom, but I have to look after my body so I can handle the physical challenges of sailing the boat.

Structuring the day with mealtimes and breaks from sailing is equally important. I’ve got some playlists and electronic books on my smartphone, and my friends gave me a selection of television series to watch, including Game of Thrones. Mostly though the adrenaline of the race overcomes any boredom or frustration, and raising money to save children’s lives boosts my morale.

How are you saving children?

I’ve been involved with Initiatives Coeur since 2015. The charity helps children from developing countries who were born with heart defects by flying them to France for life-changing surgery that isn’t available in their country.

I volunteered for a week with one of the medical teams that are sent out pre treatment to check that the children have the correct diagnosis if the local doctors aren’t able to confirm this. Now I spend a lot of time with the kids when they come to France to stay with their host families, and I’ve even been in the operating theatre and watched the open-heart surgery.

It costs €12,000 to save one child’s life, and I’m grateful to have three amazing sponsors who are donating whenever the charity’s social media pages gain a follow or their posts are shared for the duration of my trip. Using notoriety to raise money and awareness for important charitable causes is the future for top level sports, and I’m grateful that I can use my sport in this way.

Photography: Michel Slomka

Photography: Michel Slomka

Photography: Michel Slomka

Photography: Sophie Anita

Photography: Michel Slomka

Are you connected to the other contestants, your team and the world at large?

Yes, very! In my previous Vendée Globes the data was expensive and we had minimum communication outside the boat. But in 2020/21 satellite airtime is more affordable and we have WhatsApp, which I’ve been using to keep in touch with my sponsors, my shore team, my competitors, my family and my partner Romain, who has also been racing. It’s great to be able to share the adventure with the world by sending videos, images and stories from on-board.

Can you compare this race to your previous ones?

Each Vendée Globe I’ve taken part in has been a unique and incredible adventure. The first time I competed I finished fourth, and I was only an hour and 20 minutes from being third place and on the podium. I was in an old but reliable boat, which was easy to sail, and there was no expectation or pressure on me. I remember it being such a fun race, and it’s also the result I’m most proud of.

The second Vendée Globe was my saddest because I broke my mast and had to abandon the course. Getting my damaged boat back to France was a big adventure in itself, but it was disappointing not to have sailed beyond the North Atlantic.

Going into the 2020/21 race I wasn’t one of the favourites on paper to win, but until the Cape of Good Hope I was in the leading pack with a really good position and time. My boat isn’t new but it is amazingly powerful, and I was racing intensely. Then sadly I hit something – I still don’t know what it was – and there was so much damage to the boat that I had to haul it out of the water in Cape Town to fix it.

How bad was the collision?

I was sailing about 18–20 knots at night when the boat came to a standstill. It was like driving into a brick wall. The keel had collided with something in the water, and everything in the boat flew up and forwards, including me, my dinner and all the items that weren’t secured inside the boat. Some structural areas around the keelbox were badly cracked, and I hit my ribs on a ringframe and broke them.

I hurt myself. I was really scared, and I wanted to get back out there to get over what had happened

It’s a situation you never want to be in, but when it happens your body goes into automatic. The fear comes afterwards when you realise what’s happened. In the moment I couldn’t feel my broken ribs, and I acted instinctively on my training and experience. I was worried that my keel would fall out, so I slowed the boat and got my sails down to avoid the boat capsizing. Then I put the boat on the safest heading relative to the seascape, which was pretty huge. Finally I checked the boat and contacted my shore team to let them know what had happened and where I was, in case things got worse.

The keel remained attached and intact, thanks in part to reinforcements we’d made to the boat following feedback from Alex Thomson, whose keel fell out the bottom of his boat in 2019. And although I was very unlucky to hit something, I was lucky to be where I was – only a few hundred miles from Cape Town, with the wind in the right direction.

What motivated you to continue?

My whole shore team flew out to Cape Town, and many locals rallied together to help us. Once you’ve stopped and had outside assistance, the sport side of the competition is over and you have to abandon the race. But I realised that it was possible to fix the boat quickly and that I would be able to resume the course and complete the lap around the planet.

We’d been preparing for the journey for over three years, and I wanted to honour this commitment, continue the adventure and raise more money. I also needed to overcome my fear. It was a big crash.

I hurt myself. I was really scared, and I wanted to get back out there to get over what had happened.

Does sailing the course feel different when you’re not racing?

It’s been a long month and a half since I left Cape Town. In the first few weeks, whenever I started going fast at night I kept thinking about the collision.

The Southern Ocean is freezing, full of storms and very remote. You’re lucky if there’s a boat within a three-day radius, and you’re not within helicopter or airplane reach. We’d fixed the boat as quickly as possible so I wouldn’t be too far behind the last skippers in the race, but there was still an obvious gap, and I missed the safe feeling of having other competitors around me.

Being behind the fleet and out of the race, I also lacked the adrenaline and drive I’m used to. It’s a lot harder mentally than being in the race, and I’ve learnt a lot about myself and what motivates me. There is a silver lining to being out of the competition, though: I can now choose to slow down, look at the view and enjoy the sailing more.

Are you intending to enter the next Vendée Globe?

Most people still on the boat (as I am now) say, ‘No, I’m never going to do this ever again.’ Then we land, and a few days later we’re planning the next one. However, this has been my toughest race, and I scared myself so much that I really don’t know at this stage whether I’ll be able to do it again.

Where are you now?

I’m going to pass the equator today back into the northern hemisphere. The sailing conditions are wonderful – it’s hot and there’s a nice breeze – but I just want to get home. It was frustrating to see the leaders finish the race, knowing that I should have been there. Since then time has dragged.

My boat is also getting tired. There are some pretty tough conditions in the last stretch of the race – we still get storms in the North Atlantic in winter – and I’m worried about parts breaking. I’m therefore running a bit below 100% performance to look after the boat and myself.

What’s the first thing you’ll do when you land?

Spend time with my nine-year-old son Ruben and my partner Romain, who finished 14th in this Vendée Globe. I’m looking forward to celebrating Romain’s race and my lap around the planet, and to finding out how many kids’ lives I’ve saved in total. When I land I’ll go see some of the children who are already in France having their treatment. It’ll be a wonderful reward to see their smiling faces.

Sam finished the course on Friday 26 February 2021 and raised enough money to save 103 children. On the Initiatives Coeur Facebook page you can watch Sam’s video diaries from her boat.

Sam celebrating finishing the race in the channel at Les Sables D’Olonne, France, on February 26, 2021. Photography: Jean-Louis Carli/Alea

Written by

Sam took her first steps on her parents’ boat and spent family holidays sailing. Straight after graduating from Engineering, she began her competitive career as a yachtswoman and has taken part in three solo, around-the-world Vendée Globe races.