Johnian magazine issue 52, spring 2024

Urban resilience and disaster recovery

Prachi Acharya (2015) works for the United Nations Development Programme as a specialist in urban resilience and recovery preparedness. After completing a degree in Architecture and having worked for some time in the field, Prachi came to St John’s to pursue a PhD at the Centre for Risk in the Built Environment. In this article she discusses the importance of effective disaster preparation and how to improve response and recovery in the wake of these events.

Please tell us a bit about your background.

Born in coastal Odisha and raised in Delhi with modest means, I witnessed first-hand the value of public service. My father’s unwavering commitment to improving healthcare in India as a public sector clinician, especially for those living in poverty, deeply influenced me, and it continues to define my approach as a built environment professional today.

With an interest in combining sciences and arts to improve people’s wellbeing, I was fortunate to study Architecture at the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT) University, Ahmedabad. Admission was highly selective, with only five coveted spots each year for students like me from other parts of India. What set it apart was its pedagogy; shaped by Balkrishna Doshi, 2021 Pritzker Prize winner (akin to the Nobel Prize in architecture), it focused on the significance of everyday life and evidence-based choices in design, and humility in the purpose and process of building.

What first interested you in risk planning?

At CEPT I found purpose in addressing the challenges of affordable urban housing, particularly looking at climate and disaster resilience. Learning from people using scarce resources to improve living conditions motivated me to go the extra mile and informed my undergraduate design and research work, which was recognised through multiple awards and a gold medal. Already I realised that risk planning was integral to the building process for creating safe, usable and cost-effective structures that meet the needs of communities. For me, its importance was underlined by the 2001 Bhuj earthquake and 2006 Surat floods in the region. These not only shaped disaster-risk-reduction efforts in India but also our teaching, with our tutors deeply engaged in the post-disaster reconstruction and recovery processes. This certainly influenced my research at graduate level, which aimed at integrating low-carbon and disaster-resilient construction practices, and later my career choices including my current work with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in West and Central Africa.

What inspired you to pursue a PhD at

Cambridge?

Prior to embarking on a PhD, my city- and community-level work as an architect and urban planner provided opportunities to question current practices and the status quo. My desire to better understand the ‘why’, to find solutions and to increase meaningful impact is what led me to consider reading a PhD as a mature student. I had never imagined that I would study at Cambridge. I was fortunate to have strong mentors, including in my family, who strongly encouraged me to apply.

Studying at Cambridge was a great choice for my interdisciplinary research, with the Centre for Risk in the Built Environment, Centre for Development Studies (POLIS), and Centre for Sustainable Development (Engineering) each having their own strengths, distinct perspectives and fantastic professors!

Researching the implications of financing, governance and design on the people benefitting from the world’s largest welfare housing scheme in flood-risk areas in India made me realise that seeking useful solutions often begins with asking slightly different questions. Although I started my research considering building regulations and their clear link with disaster resilience, I soon realised that the challenges people faced needed looking at from a political economy perspective. Answers thus came from diverse disciplines, opening doors for tremendous personal and professional growth.

As the cherry on top, my spouse – also a Johnian – had secured a place in a different department for his PhD, so it was an exciting (and challenging) family journey to make! I remain profoundly grateful for the unparalleled support that St John’s College offered me and my young family during this time, without which it would not have been feasible to return to academia.

What are your current responsibilities at the United Nations Development

Programme?

I work for UNDP’s West and Central Africa Hub and am embedded in the regional ‘Sahel Resilience Project’, which uses disaster risk reduction as a means for risk-informed development solutions in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal. The project works in four specific areas: first, to improve national disaster databases and connect with regional platforms to better inform anticipatory actions for reducing loss and damage; second, to improve policies and public finance expenditure for risk reduction and resilience building; third, to better prepare for disaster recovery; and fourth, to improve territorial planning to address spatial inequalities between urban centres and enhance local capacities in secondary cities.

My responsibilities include technical and analytical inputs, and sustainable development policy formulation and implementation with continental, regional, national and local government institutions. I support training, provide oversight for assessments, co-ordinate with partners and colleagues across the project countries, conduct regional team planning, reporting and budgeting, and write proposals for grants and funds. None of this is singlehanded; it requires close collaboration with regional institutions and national and local governments, and I am lucky to work with excellent professionals in these institutions and within UNDP itself.

What sorts of projects do you work on at UNDP?

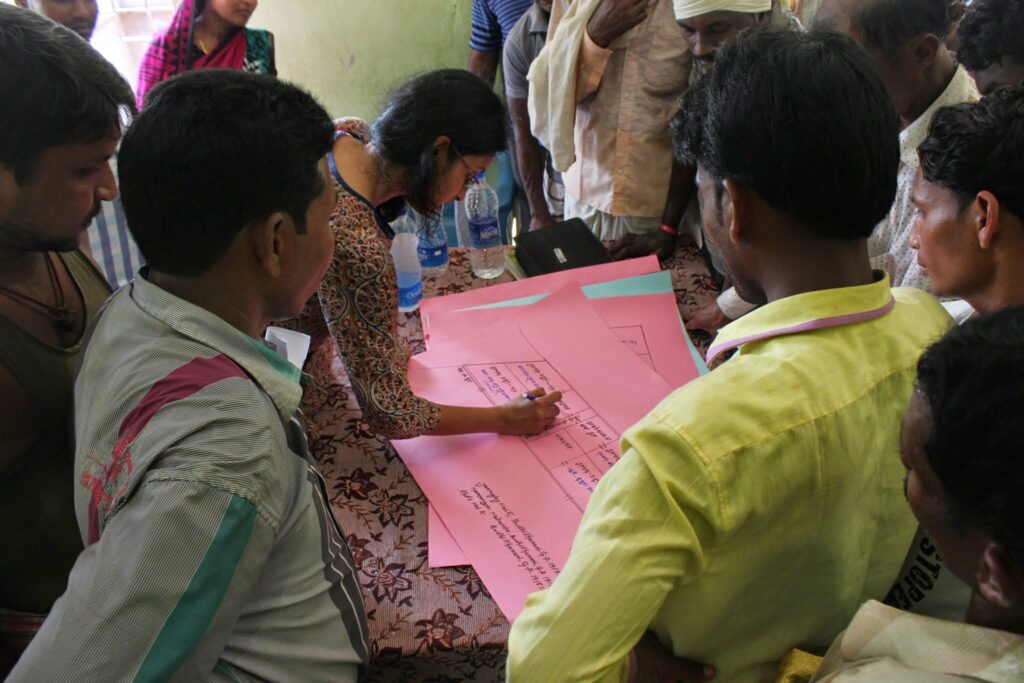

My work focuses on improving disaster recovery preparedness and urban resilience in the region mainly through increasing access to tools, methods and data analytics, improving capacities and facilitating dialogue between governments at regional, national and municipal levels.

We have supported governments to establish national disaster databases that provide critical

baselines for inclusive disaster recovery planning and helped to enhance government capacities in post-disaster needs assessment and recovery planning. This led to the establishment of a regional pool of experts from 15 West African countries who can be deployed to support governments in disaster recovery. We are complementing this by analysing disaster recovery priorities from these countries, including those contending with conflicts. Based on the analyses, and in collaboration with regional and national institutions, we are developing a roadmap for improving recovery preparedness in the region, outlining concrete actions for institutions, financing, implementation and, importantly, monitoring and evaluating systems for effective disaster recovery, including through transboundary risk planning.

For urban resilience, I have worked at the continental, regional, national and local levels. Continentally, I provide technical advice for developing a continental Africa Urban Resilience Programme – led by the African Union Commission – which focuses on early warning and action, disaster recovery and risk-informed urban development among other aspects. Regionally, with UN-Habitat, I oversee the collaboration with national governments to analyse spatial data on infrastructure and services across nearly 500 Sahelian local administrative units, which can help prioritise interventions for risk-informed regional planning. At the local level, I support Sahelian municipalities in intermediate cities to develop urban resilience action plans and help them to access funding for its implementation. With the continent urbanising faster than any other, African cities and urban centres are pivotal to the global conversation on sustainable and resilient urbanisation.

The role challenges me with a range of responsibilities, diverse fields to learn about and engagement with all levels of governance. The interdisciplinary training from my PhD is ever so useful for this! I am hopeful that it contributes, if only in a small way, to improving our understanding of the choices to better prepare for, mitigate and reduce exposure to hazards.

Which areas of your work are particularly

interesting to you at the moment?

I feel excited about the potential of cuttingedge digital systems that utilise spatialised

disaggregated data for early warning and action, sustainable investment and planning decisions. Although this serves as an initial step, there is still some way to go to ensure that communities and local governments gain more agency in its design, use and application.

Beyond digital systems and capacity building, we need to consider the context of implementing risk-reduction measures and the factors influencing stakeholders’ decisions. For this, designing preparedness systems and promoting resilient practices requires recognition of how end-users use risk information, and we need to support them in considering the trade-offs of their decisions.

What are your hopes for the future?

I am eager to learn from, soak in and contribute to wherever I end up next! So far, I am excited about helping with access to finance, which is a key impediment for many urban centres to implement their resilience priorities. To contribute in that regard, it will be absolutely critical to inform urban climate finance by closely examining municipal-level budgetary decision-making processes, paying special attention to small and intermediate cities. Currently, more than 60 percent of Africa’s growing population is situated in urban centres with fewer than one million inhabitants. These are the fastest growing urban centres in Africa, which can increasingly strain the capacities of local governments to provide basic services and manage increased exposure to hazards.

I would like to see closer engagement and greater collaboration between countries in Africa and South Asia, who have much to learn from one another about harnessing not just public but also the private sector to enhance urban resilience, reduce losses and save lives. I hope to find ways to strengthen this relationship.

Finally, I would love to collaborate more closely with academics. Large international organisations typically have access to a vast network of resources which, when combined with expertise from the academic world, can foster valuable exchanges, influence policies and enhance impact by addressing disaster risk reduction, one of the most pressing challenges worldwide.

Written by

Prachi works for the United Nations Development Programme providing specialist technical and strategic advice to governments, institutions and communities seeking to improve disaster preparedness and recovery.