Johnian magazine issue 46, autumn 2020

Playlist: a surgeon’s song selections

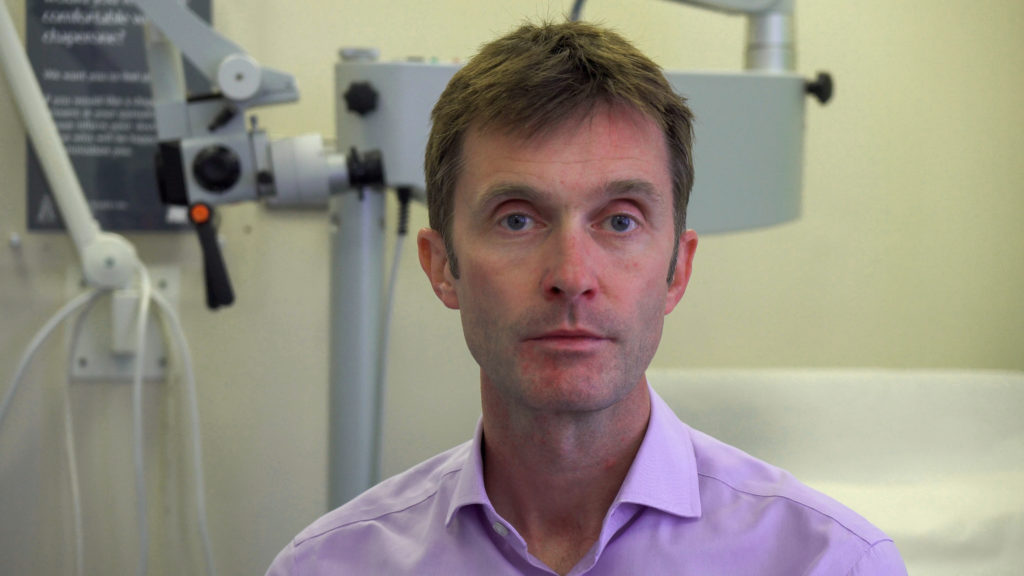

Consultant laryngologist Declan Costello (1991) talks surgery, singing and studies into the transmission of COVID-19.

Arriving at St John’s, and in particular joining the Choir, was a real eye-opener for me. I had sung in choirs at school, but singing at St John’s was a significant step up in both the standard and the professionalism.

As an undergraduate I read Music, but with my background in science (A levels in Maths, Physics, Chemistry and Music), I found that the essay-writing didn’t come naturally. Both of my parents are doctors, and I was halfway through my degree when I realised that I wanted to study Medicine.

Having graduated from St John’s, I went to Charing Cross Medical School (which subsequently became Imperial College) and worked my way through a number of different jobs as a junior doctor – plastic surgery, orthopaedics, A&E and ENT (ear, nose and throat surgery). I enjoyed ENT, and I started specialist training in 2003.

ENT is divided into sub-specialties, and it made sense, with my background in singing, for me to specialise in disorders of the larynx. I now spend most of my time treating patients with voice disorders, and I have a particular interest in treating singers. It is an immense privilege to treat professional singers – many of whom I have been listening to for years.

I still very much enjoy singing. I was previously an alto, but I’ve lost the ‘counter’ in ‘countertenor’ and now sing as a tenor. I perform with several different groups, including Polyphony and the Holst Singers.

I find that singing is a superb release from daily work, both physically and mentally. And on a practical level, it is wonderful to switch my phone off during a rehearsal or a performance: it is one of the few times when I’m entirely uncontactable.

We know that there are demonstrable benefits in terms of mental health, and there is increasing evidence about the respiratory benefits of singing. In fact, there is a research project running with the English National Opera at the moment looking at singing as a form of respiratory rehabilitation for coronavirus survivors.

I find that singing is a superb release from daily work.

The pandemic has had a huge impact on my work. In March 2020, as the lockdown began, we had to shut down all of our elective clinical care, focusing solely on emergencies and cancer work. At that time, there was a significant concern that healthcare workers (and, in particular, ENT surgeons and anaesthetists, who were close to patients’ airways) were at risk of contracting coronavirus from patients.

I worked with my wife Marion Palmer (1993) on the Covid Airway Screen, which is a simple means of preventing droplet contamination when intubating patients or working on the mouth. It was rapidly developed with a Crowdfunder campaign, and we were able to distribute the screens around the country free of charge.

Singing has been hit particularly badly by coronavirus. At the start of the pandemic there were clusters of COVID-19 centred around choirs, which rapidly led to singing being shut down (and, by extension, the playing of wind and brass instruments). Around May singing was labelled as a ‘dangerous’ activity, and a negative narrative emerged about singing despite a lack of scientific evidence about its potential risks.

In early July bars and restaurants were starting to open up again in the UK, and many singers felt that it was unreasonable that singing was being held back when thousands of livelihoods were on the line.

When comparing loud singing with shouting, singing does generate more aerosol, but not vastly more.

Along with other ENT surgeons and respiratory doctors, I teamed up with the Bristol aerosol group (led by Professor Jonathan Reid) to quantify the amount of aerosol generated by singing. We wanted to work out whether there was genuinely an increased risk of spreading coronavirus by singing compared to speaking, shouting and breathing.

The PERFORM study found that singing and speaking do indeed generate aerosol, and that loud singing and loud speaking (ie shouting) generate vastly more aerosol than quiet phonation. We also discovered that when comparing loud singing with shouting, singing does generate more aerosol, but not vastly more.

As a result of this study and another from Porton Down, the UK government opened up public performances in mid-August. The music industry is still in a very precarious state, but at least some performances are now happening, and it’s wonderful to see that the Choir of St John’s is up and running again.

Declan’s playlist choices

Bach, St Matthew Passion

(Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra, 1989)

I would guess that most choral singers would have the St Matthew Passion high on their list of favourites. There are certainly few pieces of music in the repertoire that are as moving.

The recording by John Eliot Gardiner and the Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra was the first I heard, and remains one of my favourites. There isn’t a single aspect of the performance that is not fabulous.

It never ceases to amaze me that Bach worked at such a rapid pace when composing: the music all seemed to be pre-formed in his head, and he simply had to write it down as quickly as his hand would allow.

Judith Bingham, The Drowned Lovers

(Tenebrae, 2016)

In recent years, choral music has flourished around the world. We are living in a particularly vibrant time for choral singing, which makes it all the more poignant that singing at the moment is so limited.

The standards of singing seem to be improving all the time, driven by undergraduate choirs such as the one at St John’s, and by many professional choirs such as The Sixteen, the Tallis Scholars, Ora and Tenebrae. There have been some fantastic new choral compositions in the last few years, and this is one of my favourites.

It works as a fabulous mirror image of The Bluebird by Stanford.

William Byrd, Mass for four voices

(Tallis Scholars, 1985)

Whenever I hear Byrd’s Mass for four voices, I’m transported back to a nervous Sunday morning in October 1991. This was the first mass I sang at St John’s when I arrived, and remains one of my favourite pieces.

The intimacy of the music stems from the fact that it was written for private performance. Byrd was aware that he was taking a great risk in participating in Catholic liturgy under the regime of Elizabeth I, when it was forbidden to do so, and these masses (there are others for three and five voices) were written for clandestine performances in private houses.

This particular recording by the Tallis Scholars is the first I heard, and was released in the mid-1980s. I was particularly taken with the alto line, which was sung on this recording by Michael Chance, a great figure of inspiration for countertenors of my generation.

Joby Talbot, Path of Miracles

(Tenebrae, 2006)

I was at school with Joby Talbot, and it has been fantastic to watch his meteoric rise as a composer. This unaccompanied choral piece, which follows the Catholic pilgrimage to Santiago, is breathtaking in its scope and complexity. The piece requires an incredibly high standard of singing, and Tenebrae are superb on this recording.

The first performance was meant to have been in July 2005, but the London bombings meant that the performance could not go ahead. I was lucky enough to hear a performance in 2017 in St Bartholomew the Great, which is where the postponed first performance took place.

Peter Gabriel, Don’t Give Up

(1986)

The album this song is from – So – takes me back to my early teens. Having listened to this CD, I worked back through Gabriel’s career to his releases with Genesis. As a teenager I was a bit of a Genesis groupie (probably not a very fashionable admission nowadays…) and I loved this album. The drum playing of Manu Katché particularly appealed to me, as I was a very amateurish drummer back then.

Peter Gabriel’s writing was always strikingly original, and his songs were unlike anything else being released at that time – especially in his use of musicians and influences from around the world. Also, his ground-breaking first four albums were all called Peter Gabriel, which amused me greatly.

Written by

Every issue of Johnian magazine includes a playlist feature article, in which an alumnus/a submits their top tracks alongside details about their lives.