Ross Sharpe (1986) studied Architecture at St John’s and is a member of the Beaufort Society. He is a Director of Yiangou, an architectural practice which was the subject of a SkyArts documentary, The Art of Architecture, earlier this year.

We all have significant moments in life. Two of mine were about what I wanted to do as a job and were separated by nearly 20 years.

The first was at four years of age, standing in my little kilt and looking very smart for the owner of the serene Georgian house my builder-father had just finished renovating. As I gazed at its classical symmetries, I knew at that moment and beyond any shadow of a doubt, I wanted to design things just like that one day.

The other was at university, in the midst of contemplating a doctorate on some obscure topic of architectural theory, when a wise friend simply said ‘do you want to do it yourself, or do you want to spend years writing about other people who have done it?’ Coupled with this insightfulness, my everlasting thanks goes to a great guru in our department at that time – the immortal Dalibor Vesely

– who encouraged me to be a doer. Thus the direction of travel was sealed for a career in which I seem to have had the good fortune of building some successful things, and others maybe not so…!

Sadly for me, life is never guilt-free and I often question why I might have done things in a certain way. The rigorously pro-modernist ethos at Cambridge was deep-seated and conspired to beset any youngster’s biggest complex, their moral compass. So, it has at times seemed like a long, lonely walk to try to deviate from what I perceived to be expected. However, even plagued with self-doubt, I am proud to be one of a little gaggle who have been naughty enough to break away from the conventions of those days at Scroope Terrace in the 1980s. Particularly because the world of architecture was terrifyingly divided into camps, which at times were quite entrenched.

It is gratifying to now see students and practitioners coming through the system who seem to value looking at the richness of the past as a means to inform the future

For nearly the entire duration of the Faculty of Architecture’s existence, the idea of tradition or continuity was frowned upon or actively beaten out of generations of students at Cambridge. It is fantastic that the Ax:son Johnson Centre for the Study of Classical Architecture was founded in 2021, and it has been admirably led by a distinguished Johnian, Dr Frank Salmon. It is gratifying to now see students and practitioners coming through the system who seem to value looking at the richness of the past as a means to inform the future.

For my own part, I’ve always been immensely grateful to have mixed with the polymath teachers and students who made those years at St John’s so enjoyable, and I have always tried to eschew the notion that there is a right or wrong way to do things.

Above all else architecture must be lyrical

I think we have to acknowledge that there is still a popular desire in much of society to find some kind of comfort in the proportions and rhythms of history. It would also be naïve of me not to recognise that there is another highly potent and easily recited mantra that says that pastiche is the enemy of progress.

So, I feel it is entirely possible to design a traditional building for one set of contexts and a contemporary scheme for the next. I guess you could say it is only with years of exposure to the patronage and commissioning process that you begin to understand the complexity and contradiction of our common humanity.

With few exceptions, the buildings I have designed have been for individuals or institutions with large pockets, and I wonder how it must have been for those young post-war architects with utopian visions of building a better world, but on a shoestring. The reality is that in our postmodern age, as in the other ages of capitalism, it is the wealthy who are the patrons. In designing homes for this particular section of society, my solace has been that wealth can support craft and artifice. With that comes a potential resurgence of skills and talents and the money ‘goes around’ for the greater good.

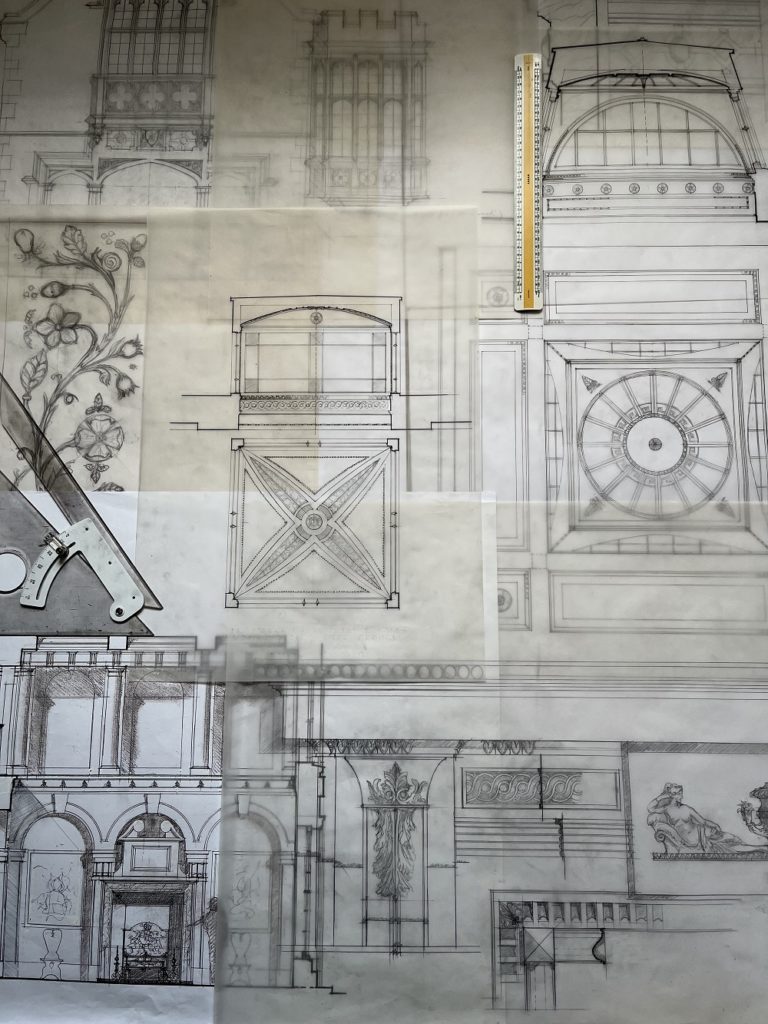

Above all else architecture must be lyrical. When I came for my interview in the 1980s, I thought I drew in a way that all students did. Apparently this wasn’t the case and with some embarrassment my portfolio was passed around all the year groups for inspection – the tutors believing there was something of value in what they saw. Even now, I believe in a link between the drawing and the soul, to a degree that can perplex the yearly intake of students at our firm.

I still only draw by hand, in an office which relies heavily on CAD technology for grunt work. There is nothing wrong with these systems as drawing aids, but along with many of my generation, I believe that many youngsters are designing the way they do because they can, rather than seeing the computer as a tool. Luddism is a cruel expression, and the arguments about the dangers of the machine have been rehearsed to a point way above my philosophical pay grade. I, the romantic, remain unconvinced.

I suppose it was an understanding of my beliefs that aroused the interests of the SkyArts advisers when we were approached to make an episode of The Art of Architecture last year.

Where many practitioners have no issues courting publicity for their work, or have a client base who see value in the awards process, my firm has always put client confidentiality and discretion at the top of its professional culpability agenda.

This has meant that very, very few buildings have ever been, or are likely to be, seen by the public. It was, thus, to our relief that a few private individuals reconsidered, even though my personal favourites were the ones whose doors were permanently shut to cameras… or in one case burnt down!

Whittling down the list to seven buildings and trying to find a good mix between the sort of things favoured by the RIBA, as well as more classical and traditional work, it still came as a bit of a surprise when the series producer chose to focus on me at my drawing board (my outfit styled by my nine-year-old daughter to look more like Lutyens than Liebeskind!).

None of the architects featured in the series were given the opportunity to see the programmes ahead of airing. With retrospective naïvety one of my colleagues asked if Lord Foster or Sir David Chipperfield had been awarded this courtesy. A firm ‘no’ came the reply! This may explain why I have sleepless nights about the editing of the countless hours of filmed interviews and the choice of content and shots – which I fear may have not shown the best of the buildings. It made for a bit of a curate’s egg of a show and I have some regret that some of my colleagues, including my brilliant great friend and collaborator for the last 25 years, Christopher Draper, were not given a bigger share of the limelight. However, I am pleased the programme has caused interest and debate.

Ross funds the Sharpe Drawing Prize which is awarded annually to a student at St John’s, and he has also pledged a legacy to the College. You can read more about leaving a legacy to St John’s here: johnian.joh.cam.ac.uk/legacy-giving

To find out more about Ross’ work you can visit the Yiangou website: yiangou.com

Written by

Ross is an architect and Director of Yiangou Architects in Cirencester. He is a member of the Beaufort Society and funds the Sharpe Drawing Prize at St John’s. During his career Ross has won several awards and his work uses a blend of traditional and contemporary design.