In 2015 wildlife film-maker Tom Mustill (2002) had an accident that would begin an obsession with whales and lead him to research how AI might help us to communicate with them. Tom, who spoke at the Beaufort Society Annual Meeting in October 2023, was interviewed by the Johnian Editor about his experience.

What first interested you in the natural world?

I always loved nature, but I grew up in London so most of the nature was in parks and gardens. The only TV programmes I was allowed to watch as a child were David Attenborough and Star Trek. So, that pretty much shaped my entire world view! At St John’s I studied Natural Sciences and I would come back from lectures and try to explain to friends on different courses things like how bivalve molluscs filtered things. I was more motivated by that than doing my essays on time!

Obviously, I have to ask about the whale! What happened and what was going through your mind?

(c) Larry Plants

I had gone to Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute to visit an engineer who was designing underwater robots. As a wildlife film-maker, I’ve always been interested in new filming tools. He was showing me self-guided submarines and the recordings they beamed back of thousands of jellyfish far out to sea.

As I was leaving the Institute, we looked out of the window and there were loads of humpbacks out at sea. You could see their spouts and an occasional breach or splash. The engineer suggested a kayak tour as the best way to see the whales.

So I signed myself and my friend Charlotte up. Charlotte had never seen a whale before and we had a great time. After a couple of hours, we were paddling back to shore in quite shallow water. Then a whale unexpectedly breached (this is when a whale leaps out of the sea). It was about one whale’s body length from us as it came out of the water.

I remember thinking, ‘It’s going to land on us and we’re going to die’.

Suddenly we were underwater being thrown around and feeling a terrific amount of energy. I learnt later that the energy required to lift a whale out of the water is equivalent to 40 hand grenades. A whale is about 30–35 tonnes.

I was sure I was gravely injured. There was no question in my mind that Charlotte was dead because she was closer to where the whale landed.

I had to swim up to the surface because it had sucked us quite far down. When I popped up I saw Charlotte’s grinning face and she was absolutely fine. And I was absolutely fine. The kayak had a big dent in it. But somehow we were ok, and, fortunately, so was the whale.

Why do you think that was?

A biologist friend analysed the trajectory of the whale and what it did with its body. Another biologist corroborated that it had seen us in flight. Their eyes work well underwater and above the surface. They can manipulate their eyeballs to compensate for the changed optics. It had likely seen us and moved away so it just glanced us with its pectoral fin and didn’t land on us directly, which would have certainly killed us.

That was in some ways just the beginning of quite a peculiar sequence of events. I became obsessed with whales.

The first was that somebody videoed the whole thing! It went viral.

What was that experience like for you?

I didn’t like it much. I was used to being the wildlife film-maker, not the subject. There were caricatures in national newspapers with George Osbourne and James Cameron in the kayak with a Jeremy Corbyn whale leaping on them and things like that. It was really disconcerting, especially because it had been a shocking, violent experience.

But I also loved it happening. It was such an impressive thing to see and to survive it was very lucky. I had a tremendous joie de vivre afterwards because I was still alive but also because the sight of this huge animal throwing itself into the sky with water streaming off its lumps and bumps was just tremendous.

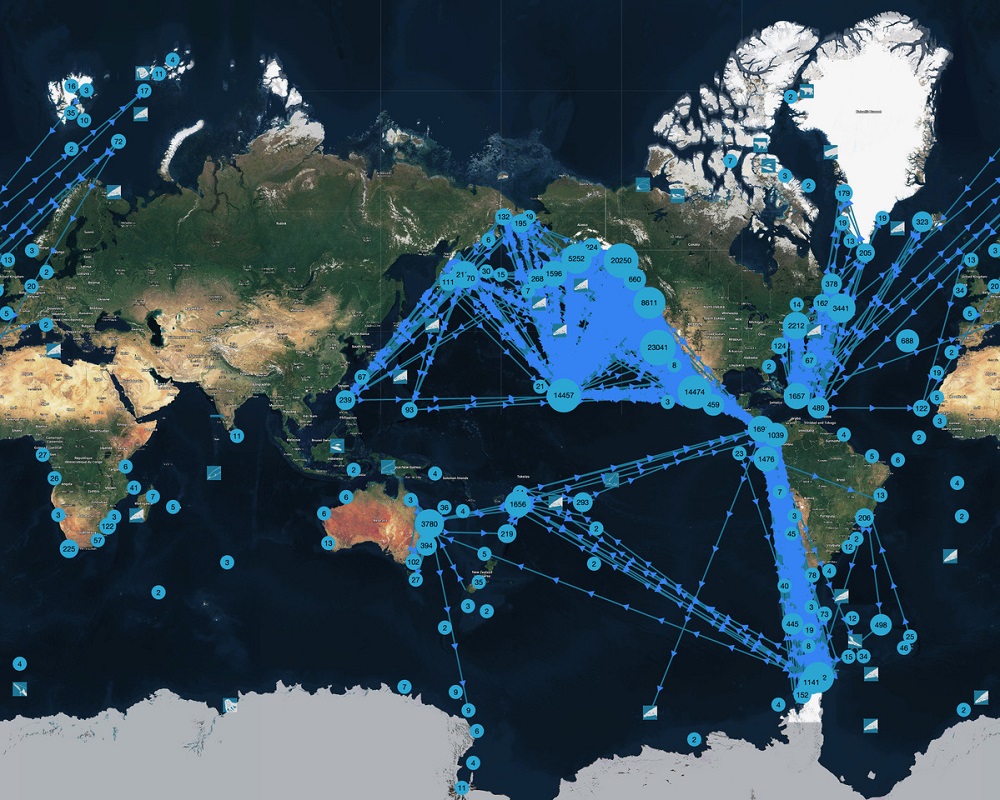

People were able to analyse the video and use AI to figure out the identity of the whale. This linked to its history so I learnt where he was born and who his mother was. Actually, I got an automatic email just last week saying that the pattern recognising tools had identified him back in Monterey Bay.

What did you make of that?

Well it’s just peculiar really. After I left St John’s, I did bird conservation in a tropical forest in Mauritius, listening for endangered birds landing in their nesting trees. I had to crane my neck to try to identify them by the rings that we put on their ankles, which was often very hard. I tried to chart how many individual birds there were and what they were doing. So the idea that whales could be automatically identified and tracked by machines was incredible.

After the whale landed on us I went on hiatus from film-making – I had been making films with David Attenborough and Greta Thunberg – as I thought that this was very unusual and the way I’d been pulled into it was too dramatic to ignore.

That’s why I started doing research. And while I was doing it, the fields just exploded as the tools became more widespread and AI itself took off.

Was AI something that you’d always been interested in from a conservation point of view?

I’m lucky that a friend I met in Cambridge, Ian, was very involved in AI (he’s actually leading the UK’s AI Taskforce now). In my first year, I met a palaeontologist called Dmitri Grazhdankin who took me on as his summer field assistant. I got a C W Brasher Award for Adventurous Travel from St John’s and went to look for fossils. We travelled in helicopters in the Arctic, rafted down rivers in the Ural Mountains and hiked through restricted areas north of Lake Baikal, Russia, looking for half-billion-year-old fossils. In palaeontology you try to understand what an animal is by its body, but nobody knew what the fossils we found were because their bodies were so strange.

I started using statistical analyses to find patterns in the relations between the fossils, because the bodies were preserved exactly as they’d lived, in whole communities. If we could analyse that, I thought, perhaps it would tell us about how they lived. Ian taught me to use a statistical tool called a Monte Carlo simulation to generate random arrangements of all these creatures on the ancient seafloor and then compare them to how they actually lived, to see if their arrangement was chance or not. It took all 25 computers in the lab, and for five hours I pressed space so they wouldn’t shut down, running each iteration of this analysis. This was a very crude but fascinating entry into the use of machines to interrogate the patterns of living organisms and find patterns that humans can’t spot by themselves.

So that thread had already been laid and it’s been running through my life. I’ve always used wildlife film-making shoots as opportunities to try new tools. I’ve filmed bat births with infrared cameras, flight dynamics with thermal-imaging cameras, and recorded giraffe and elephant communications in infrasound.

What were your biggest discoveries in that period of research?

I went to bioacoustics conferences and I saw that researchers were struggling with massive datasets. The problem previously had been getting enough information, but now recording devices are so ubiquitous the problem is that there is too much! It’s a bit like personal photos; you used to have a few albums and pretty much know all the photographs that you owned, but now you can take as many as you want and the problem is storing and organising them. Now tools can find all the photos on your phone of your mum, for example, and they’re getting better and better.

I wanted to see what happens when the pattern tools designed for humans get applied to animals. I met scientists who take tools for finding patterns in language, like the ones behind Google Translate, and apply them to non-human communication systems to see if they have anything like language. Most of the work that’s been done to understand animal communication systems involves a person working with an individual animal or group and trying to find patterns with human ears and brains and within human lifespans. However, the language models behind Google Translate and ChatGPT translate and manipulate human language without bilingual dictionaries, guidance or training, and their power comes from discerning patterns in very large datasets – datasets far bigger than a human could ever experience. So what about animal ‘Big Data’?

What do think is next for this technology?

We have learnt that many AI tools are general purpose. For example, a tool that recognises human faces also works with dogs and can even help to identify plants. It’s likely that many Johnians reading this use apps like Merlin, which identifies birdsong, or Picture This, which can tell you which plant is in the garden and how to care for it. The general-purpose nature of these tools means that we are all able to access biological knowledge and interrogate and record the world around us. As the database gets larger, we’re going to be able to find new patterns.

Whether other species have communication systems that relate to human language is something we can only learn by observing their wild lives. Lots of people (including philosophers and linguists), who have never spent any time watching animals, have strong opinions on whether other species have language. To me that feels like having a strong opinion on what black holes are like and whether they are outside of our galaxy, having only studied our galaxy. However, the big datasets could start to show us what kinds of structures exist. We may find patterns in animal communication that are very like our own, or perhaps they will be totally different.

In my book I compare this to van Leeuwenhoek’s discovery of the microscopic world. Before this we didn’t realise that there was life at the tiny scales that we couldn’t see, so we assumed it wasn’t there. Today we don’t know what communication galaxies exist on this planet, but with these tools we may be able to perceive and find our place in them.

Are there risks to this?

We’re going to be confronted with some big decisions. As we learn how other species communicate that may also allow us to manipulate them. There’s room for bad actors there.

We can already deep-fake humans and we can probably deep-fake whales too. Are we creating new avenues for cultural pollution? If we start playing whales random noises that sound like things they say without knowing what they are that could be very damaging. We need to think about how we apply these tools. I think the best route is to listen for a long time before we start saying anything ourselves.

There’s a lot of discussion about the intersection of AI and nature, both from a philosophical and a legal perspective. Many AI models have been trained purely on human cultural datasets and human culture currently does not highly value the rest of the living world. How can we help to align their values with evaluation of other species too? What do we need to think about before allowing these models to have access to masses of nature imagery and the cultures of other species? Who, if anyone, can claim to own or speak for this information? These are huge questions but they are rushing at us fast.

Do you think there are opportunities for AI to help us to overcome these prejudices?

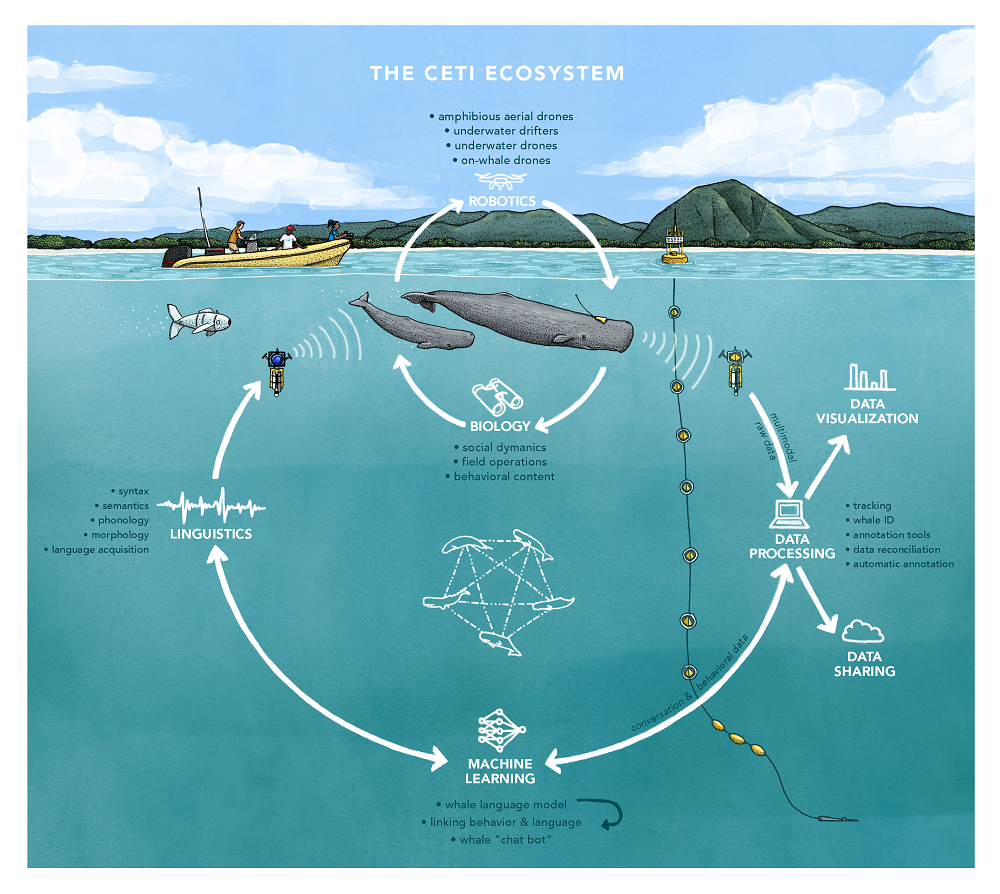

Well, very generally, coupling larger datasets with AI analysis is already allowing the study of animal behaviour to become more statistical, and that means you can test hypotheses. There will be new opportunities to find out what other species might be doing or saying. For instance, last month a sperm whale was born in Dominica, and it was filmed with drones from above and recorded underwater from two different audio sources. The female sperm whale’s mother, sister and other offspring were all there. They were clustered together and were all vocalising. AI tools have already separated out the vocalisations, including that of the newborn whale, and they will be able to follow the newborn as it learns to speak.

In a few years this project, CETI, should have enough examples of sperm whale communication (they already have doubled the world’s recordings of sperm whales) to run some of the large language model AI tools. Insights from these, combined with observations of the whales’ lives and metadata about what else was happening, will allow linguists, ethologists and other specialists on CETI’s teams to form and test hypotheses and better understand that particular whale culture’s way of communicating. Perhaps they will even be able to ‘decode’ them into something we could appreciate.

Discoveries like this are going to create some difficult moments for humans because most of us believe ourselves to be inherently different from other species, and one of the things this rests on is the Descartean belief that language is only for us and that in using it we display our unique rationality. But if we find that other species are communicating, where does that leave us? What is special about us? And how does it affect our responsibilities toward other species?

When Roger Payne released an album of humpback whale song in 1970 it went viral. That’s why the Save the Whales movement was so successful, not because they’d analysed how many whales were being killed or written down what they did, but because they played their voices to people. People were moved by the beauty of the songs and, when told that when analysed they shared characteristics like rhyme, rhythm, verse and chorus structure, and performance evolution with human songs, it changed how we saw them. Suddenly people cared about the whales and marched to protect them. Empathising with other species forces us to inconvenience ourselves more on their behalf. These could be the only other beings with whom humans could ever communicate.

Animal communication research has never had funding on anything near the scale of the Large Hadron Collider or the James Webb Telescope. How foolish and sad would we feel if we found all the black holes and sub atomic particles but forgot to speak to our only relatives when they were alongside us.

What’s next for you in all this? Where do you want your research to take you?

Recently I’ve been asked to do lots of advocacy work. I’m going to COP28 to play whale voices as a way of representing cetaceans as climate migrants and allies. The seas are warming rapidly and the cultures in the seas are changing fast. Playing whale voices seems to have a profound effect on people. So my work is moving into advocacy, and I’m trying to grapple with these philosophical issues and bring them to wider attention.

I love writing. I find it exciting to be in this world of ideas, meeting people doing fascinating work and trying to figure out how to frame things so that the readers grasp what I had the luck to experience first-hand. But I also hunger for exploration and discovery, and in film you get to do that.

I hope to pursue a PhD on the implications of communicating with other species. I’d like to do this part-time while I write my next book, which will be about analysing human behaviour through our evolutionary history as social animals. If any Johnians fancy sponsoring my research I’d be delighted! I’ve had two daughters in the last four years and what I’ve learnt from that is that humans are spectacularly caring animals. Our hands aren’t just great at holding tools and slaying one another, but at holding each other, calming and helping. We’ve evolved impressive skills to look after our groups. We tell ourselves that we want to stand out and be independent in our lives, but the evidence seems to show that what makes human beings happiest is knowing how they fit in. I want to frame that within our evolutionary context, comparing us to other extremely social, impressively caring animals.

You can read more from Tom in his book How to Speak Whale.

And to learn more about the Beaufort Society you can visit our legacy webpages.

Written by

Tom is a wildlife film-maker who has worked with David Attenborough, Greta Thunberg and Stephen Fry. He studied Natural Sciences at St John’s and worked as a field conservation biologist before moving into TV production. Tom was co-host of the environmental podcast So Hot Right Now and is the author of How to Speak Whale.