To celebrate International Women’s Day, in this feature three Johnian women discuss how undertaking sport helped them to become more physically empowered.

Katerina Gkorila (2012), Medicine

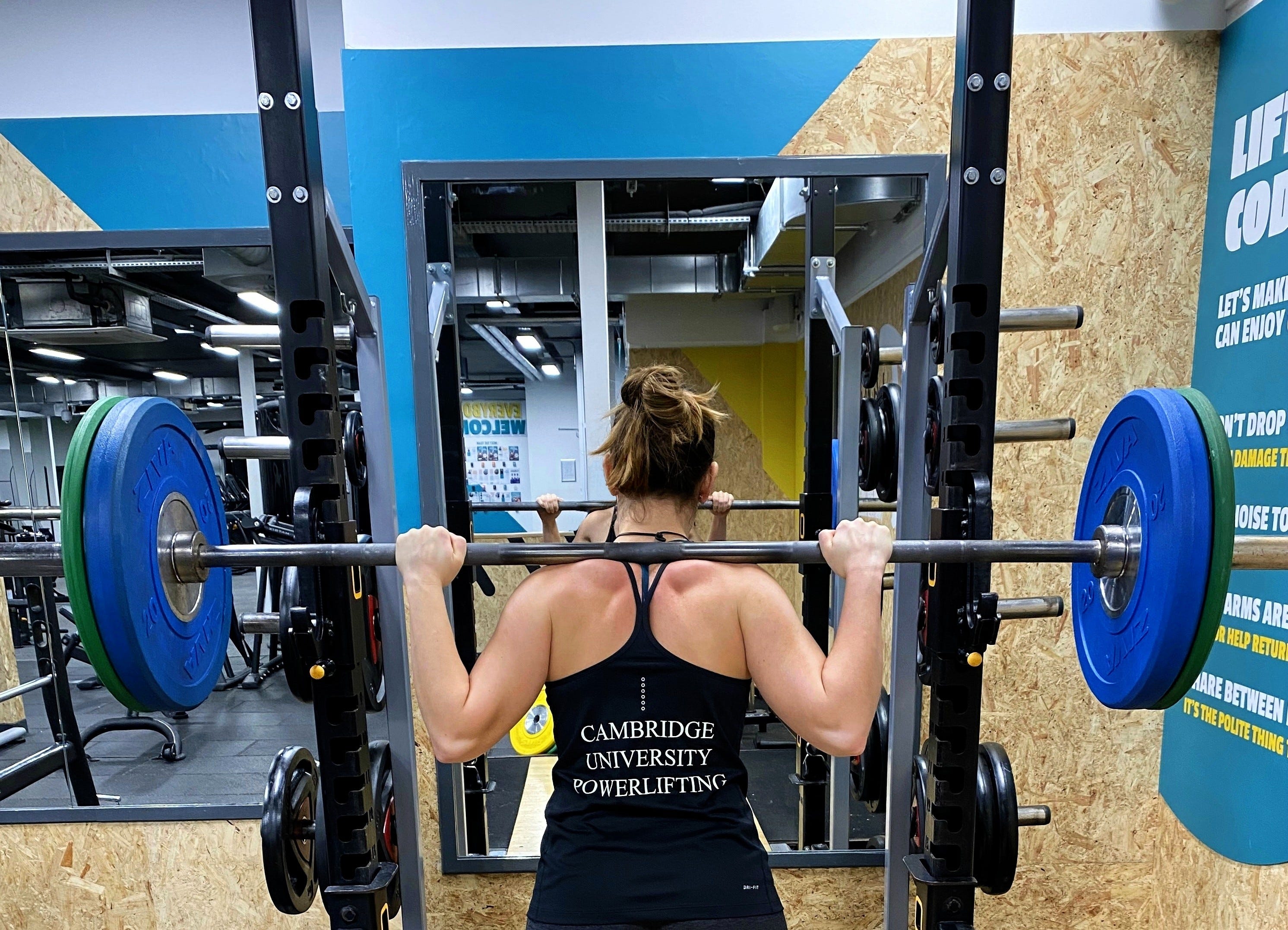

I was initiated into powerlifting when weights proved necessary for my rehabilitation following a knee operation. The weights section of the gym was male dominated and admittedly intimidating. Yet as I trained more and more, I disrupted the gender homogeneity and felt inspired to help other women feel as strong and confident as I did. From the expertise I gained at the University Powerlifting Club, I soon found myself coaching friends and peers.

In my final year I was excited to see St John’s finance an Annual Fund project where complimentary weightlifting instruction sessions for women were organised in order to create a more welcoming fitness community regardless of gender. Projects like these, and the support I received from College for both my medical research placements and as a Cambridge Bursary recipient, make me proud to be a Johnian. I will forever be grateful for the generosity of my donors, which allowed me to pursue both my degree and my sport.

Lifting improved my physical power but also built mental strength and emotional resilience, and it gave me an outlet to constantly push my limits. In a #MeToo world where we are more aware of the spread of sexual assault than ever before, powerlifting made me feel more secure in being able to defend myself, a benefit I hadn’t considered before starting.

The perseverance and discipline lifting taught me even trickled into my studies. Every single session made me more: more happy, more energised, more motivated — and less stressed in an exacting scholastic setting.

Katerina with her University Powerlifting Club teammates and training

Today, comparing looks, relationships and wealth through carefully filtered moments on social media can make us feel inadequate. However, I’d like to think that social media can also provide a platform for positivity too in introducing a space for many different role models to inspire. In the last few years there has been a move away from older visual ideals to body aesthetics which present fitness and strength as the ideal, regardless of shape, in all genders.

Everyone’s perception of beauty is unique. Aesthetic change should be underlined by love for our body and respect, according to only our own criteria and not generated by social media or the ideals of others. There is no greater way to love your body than by imbuing it with strength, and powerlifting is a terrific way to transform your body and boost your self-image before considering a scalpel. When those physical changes are paired with pride for making it through those heavy reps and seeing your body’s true potential, a love for it becomes instinctive.

When most people think of plastic surgery, they think cosmetic, which is a valid field of medicine and not deserving of the judgement it receives by the uninformed. However, in reality, the biggest area in which most plastic surgeons work is reconstruction.

As a medical student, I remember watching my mentor perform a TRAM (transverse rectus abdominis muscle) flap following a mastectomy. Muscle, fat and skin are transposed to the breast for reconstruction — it’s a minor miracle and completely changed my perspective. There is artistry in cutting, reducing, rotating or suturing tissue. It is reflected even in the original Greek etymology πλαστική (‘plastiki’) — the art of sculpting and moulding. From delicate microsurgery to major trauma work, the goal is to repair and restore form and function and improve the patient’s quality of life.

There are many — not mutually exclusive — ways of achieving the changes we wish in our appearance. I’m an advocate of healthy living, self-care and exercise, but I accept that not all changes can be achieved in the gym. Whichever way people choose to change their physique, the aim should always be self-love and confidence.

Anastasia Blamey (2018), Medicine

Gymnastics is an incredibly rewarding sport. However, my career as an acrobatic gymnast for team GB came with a gruelling training schedule, restricted diet plan and a large focus on body image. I found it difficult to be a normal teenager while training 20 hours a week. After school I would go straight to the gym instead of socialising with friends or studying. I followed a strict diet plan, which prevented me from eating out, and my Friday nights were spent getting ready for Saturday-morning training sessions and my part-time job as a gymnastics coach. I wasn’t allowed to go on holidays. While my friends and family were jet setting, I was at home training or sleeping.

The impact gymnastics had on my life meant I didn’t want to continue it at University. Cheerleading is a sport that uses my gymnastic skill in a more friendly and team-oriented way, and it proved the best way for me to continue my love of gymnastics without negatively impacting my mental health.

When I competed in acrobatic gymnastics, we could be penalised for having the wrong body type. In cheerleading there is no such discrimination. It feels like a less superficial sport that focuses more on skill and execution than image — which might surprise some!

Society tends to oversexualise females in sport, encouraging them to prioritise sex appeal over strength. For those watching, cheerleading is often reduced to nothing more than a show. But in truth we sweat, we get cuts and bruises, and more often than not someone will hobble home from training with a twisted ankle and a black eye.

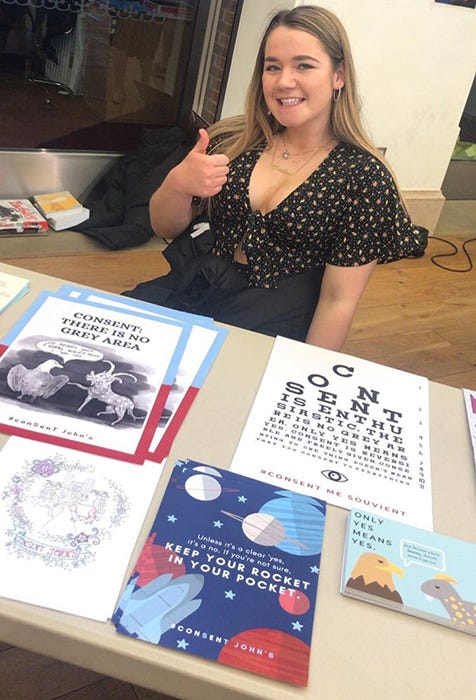

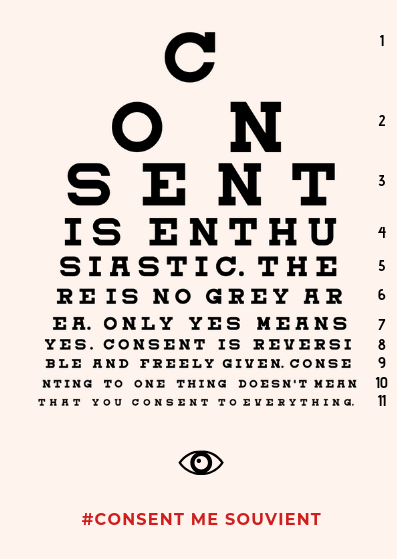

Having started conSenTJohn’s — the sexual consent campaign at St John’s — I’ve realised how prominent the issue of over-sexualising women in sport is. Performing in a cheerleading uniform is not an invitation for sexual misconduct. I cheerlead to keep strong and flexible, to improve my skills and because I enjoy it as a sport. I do not cheerlead to impress anyone or sexualise myself. Consent is explicit and not ‘implied’ by biases one might possess about someone: from the clothes they wear to the way they dance.

Anastasia with conSenTJohn’s campaign posters, design by SJC student Adi Levin (2018)

The most frequent question I get when I tell people that I cheerlead is ‘What team do you cheer for?’ It’s a common error that cheerleading is a sport in which girls throw pom poms in the air to celebrate male led games. Cheerleading is an athletic sport in its own right: we compete against other teams on a national level and are judged on skill and execution. Cheerleading routines involve tumbling, stunting, dance and jumps, and they require an extremely high level of strength, flexibility, power, endurance and balance. Many of the skills we perform as a team are very similar to the skills I used to compete when I was a national gymnast. The only difference is the stigma and preconception built by an anecdotal media depiction of the word ‘cheerleading’.

Anastasia competing at cheerleading nationals and world cups

It’s incredibly difficult to tell people I do cheerleading. I’m always greeted with negative attitudes and misconceptions about the sport, which people are reluctant to change. Many of my friends that play field sports like hockey, rugby and football believe that cheerleading is in an inferior league and remain willingly ignorant to the extreme athleticism involved. Most of the members of the first cheerleading team are ex-national gymnasts, tumblers or acrobats, and we train more hours a week than most other Blues teams.

Studies show that social support has a considerable impact on mental and physical health. In addition to the more obvious physical benefits of exercise on health, team sports come with the added benefit of building well-grounded relationships. There is a sense of esprit de corps among the team — ‘never let your flyer touch the ground’ is something we often say to improve the flyer’s trust in their bases (a flyer is lifted into the air during cheerleading stunts). I’ve found that cheerleading has had a positive impact on my mental health through bonding with my team, escaping work for a few hours a week and providing physical empowerment. Because of the nature of my medical degree, I can’t work while at University, and receiving a St John’s Studentship gave me the freedom to compete for a University team by covering the fundamental costs. My team feels like home, and I couldn’t be more grateful to be part of this squad.

Elisabeth Furtwängler (2011), History of Art

Growing up I played every sport I could. I was big into skateboarding, snowboarding, ice hockey, basketball — you name it, I did it. But my biggest love was football, which always felt like it was meant for me even though I was the only girl on the field back then. I joined my first team when I was six — there were no female teams in my town, so I joined the boys and blended in seamlessly.

When puberty hit, people started calling me ‘tomboy’, and some of my class mates would say it wasn’t ‘feminine’ to play sports, making me self-conscious and insecure. To ensure that people could see that I was a girl, I sought out traditional gender signifiers — I started dressing in pink, pierced my ears and grew my hair long. But nothing could keep me off the field. Sport made me feel confident and strong and I wouldn’t let it go.

I played for the German national football team development squad in my early teens, and, following matriculation, also for St John’s and the University women’s football team, which I captained. I even won Sports Woman of the Year in 2013/14.

Elisabeth during her time playing Blues football

I was a proud member of the Flamingos, the St John’s group of female sports captains (in contrast to ‘The Eagles’, the male captains). At the time I didn’t think much about it, but now, looking back, I wish female athletes in College had an animal historically associated with St John’s and not one chosen in 1982 because it was pink. In 2020 I wonder why there is still gender segregation for the captains. I look forward to a day when University-wide athletes of all genders (including non-binary) will be able to compete together based on skill, not biology.

I remember walking through the St John’s bar for the first time, seeing the walls covered with pictures of the men’s teams and not feeling valued as a female athlete, coupled with a lack of female role models to turn to around College. Thankfully representation has improved, but John’s could do even better.

Four years ago, my mother Maria and I founded the MaLisa Foundation, a charitable foundation to focus our work on gender equality and freedom from discrimination. We are acutely aware of how gender inequality is prevalent in all societal contexts and has a negative impact on not only women but all genders. We are committed to contributing to a positive change, so, as a family, we decided to establish the MaLisa Equality and Diversity Fund at St John’s (among our other global endeavours) to promote equality, diversity and inclusivity within College. From our work on gender representation in the media in Germany, we know that a first important step is to conduct research in order to identify, address and monitor challenges related to gender equality issues. Therefore, we funded a post for a Research Associate to investigate gender equality and diversity within St John’s in 2019. The data will serve as a basis for the development of sound solutions and projects that can stimulate structural and long term benefits for gender equality in the College.

Diversity and inclusivity are integral to a brighter future and can be achieved through strategies that include the distribution of leadership positions (we were delighted to hear that the new Master Elect is a woman); encouraging students in different extracurricular activities and subject areas; tackling unconscious bias; and preventing violence by fostering a more balanced mindset and culture that promotes zero tolerance and ensures effective response. I am happy that we can contribute to the efforts towards equity, diversity and inclusion — in sports and all other areas — at St John’s.

This article is an extended extract from this year’s issue of our annual donor magazine, The Marguerite. To see the original article (including male athletes), read more from the 2020 edition or take a look back at previous issues, visit our website. Should you have any questions about this issue, please email development@joh.cam.ac.uk.

Interviews by Jess Mackenzie, Stewardship & Development Officer