Eileen Hunt Botting (1993) is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame. Read on for an overview of her career journey in academia and find out how she works to give women writers the recognition they’re due.

In the autumn of 1992 I had the tremendous luck to win a British Marshall Scholarship for postgraduate study at Cambridge. I knew almost nothing about the place, except that it was one of the most famous universities in the world. In the stacks of my campus library at Bowdoin College in Maine, I found a book on the history of Cambridge. Flipping through its glossy illustrated pages, I stared in disbelief at the sublime and beautiful photographs of the colleges, filled with castles, moats, and daffodils. It felt as though one of Wordsworth’s poems had come to life and bloomed in the real world.

I had planned on continuing my studies in English literature at Cambridge, with a focus on Gothic novels of the Romantic and Victorian eras. My favorite writers were Mary Shelley, the Brontë sisters, and Bram Stoker. Things changed in the spring of my senior year. I took a seminar on the political philosophy of John Rawls and his critics, and Susan Moller Okin’s critique of the gender biases in Rawls’s theory of justice changed my way of seeing both literature and philosophy. From then on, my academic calling would be to give women writers their due in the field of political philosophy.

I switched my subject of study to Philosophy just prior to arriving at St John’s, fully aware that it would be far more difficult for me to learn a new field than to stay the course in my area of growing expertise. I can’t say that my academic performance at Cambridge matched the benefit of my immersion in the interdisciplinary intellectual culture and the strong social networks there. My friends from the Samuel Butler Room are still some of the closest I have ever known.

While I was not the best student, I discovered my academic vocation at Cambridge. In a tutorial on the political thought of the French Revolution with Sylvana Tomaselli, I read Rousseau, Burke, Wollstonecraft and other political thinkers who influenced or responded to the political debates surrounding the events of 1789. Tomaselli’s teaching, lecturing, and scholarship inspired me to write my doctoral dissertation at Yale on the political thought of Wollstonecraft, Burke, and Rousseau. It became my first book, Family Feuds: Wollstonecraft, Burke, and Rousseau on the Transformation of the Family (SUNY, 2006).

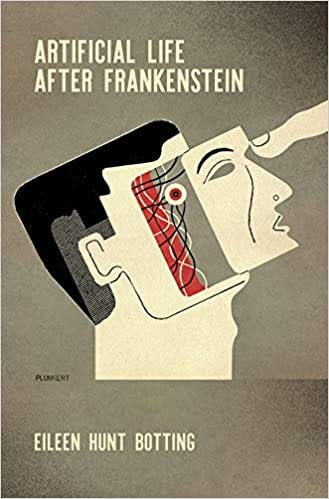

More recently my research has brought me full circle to the ideas that excited me most when I was a student at St John’s. In my forthcoming book — Artificial Life After Frankenstein (Penn, 2020) — I explore how Mary Shelley’s novels Frankenstein (1818) and The Last Man (1826) shaped a subgenre of modern political science fiction that challenges the technophobia in philosophical responses to genetic engineering, artificial intelligence and pandemics. I recently published an essay based on the book in The TLS, ‘Journals of Sorrow.’ It connects Mary Shelley’s great pandemic novel The Last Man not only to her private record of plagues and other personal tragedies, but also to our current predicament of coping with the incalculable losses of COVID-19.

In her ‘Journal of Sorrow’ — begun three months after the death of her husband the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley — Mary Shelley modelled how writing one’s own history affords perspective on the past, endowing it with meaning not only for oneself but also for others. Looking back on my time at Cambridge, seeing the way it has formed my friendships and career over a quarter century, I perceive three ideas of value to share with current students and young alumni of St John’s.

- First, follow your sense of what matters to you in your studies. The path may seem wandering and difficult — like Dante was lost in the woods at the beginning of the Divine Comedy — but trust that it will ultimately lead you where you need to go.

- Secondly, remember that the people you meet and the community you build at St John’s are far more important than any external validation of your intellectual capability while you are at Cambridge.

- Thirdly, know that you deserve all the magic that is or was the chance to live in a castle illuminated by rays of mid-winter light, with a moat, and a bridge of sighs, surrounded by fields of lilting daffodils cast in surreal shades of yellow, miraculously blooming in February, as though their bright shoots — and you too, gazing down upon them, now or then — are living, breathing, thriving elements of the poetry of Wordsworth.

The Development Office are always keen to hear what Johnians are up to. Get in touch: development@joh.cam.ac.uk