Christina Faraday (2011) is a historian of art and ideas, Research Fellow and lecturer at the University of Cambridge. Her academic research focuses on Tudor and Jacobean art, and her first book, Tudor Liveliness: Vivid Art in Post-Reformation England, was published in April 2023.

I became an art historian by accident. I’d always intended to study History at university, but a chance meeting with Dr Frank Salmon (Director of Studies in History of Art at St John’s) at a Cambridge open day convinced me that everything I thought I loved about History was really more relevant to History of Art. What I wanted was to spend my time discovering how people lived and how they thought through the material objects and artworks they produced and admired: it turned out that History of Art was the subject for me.

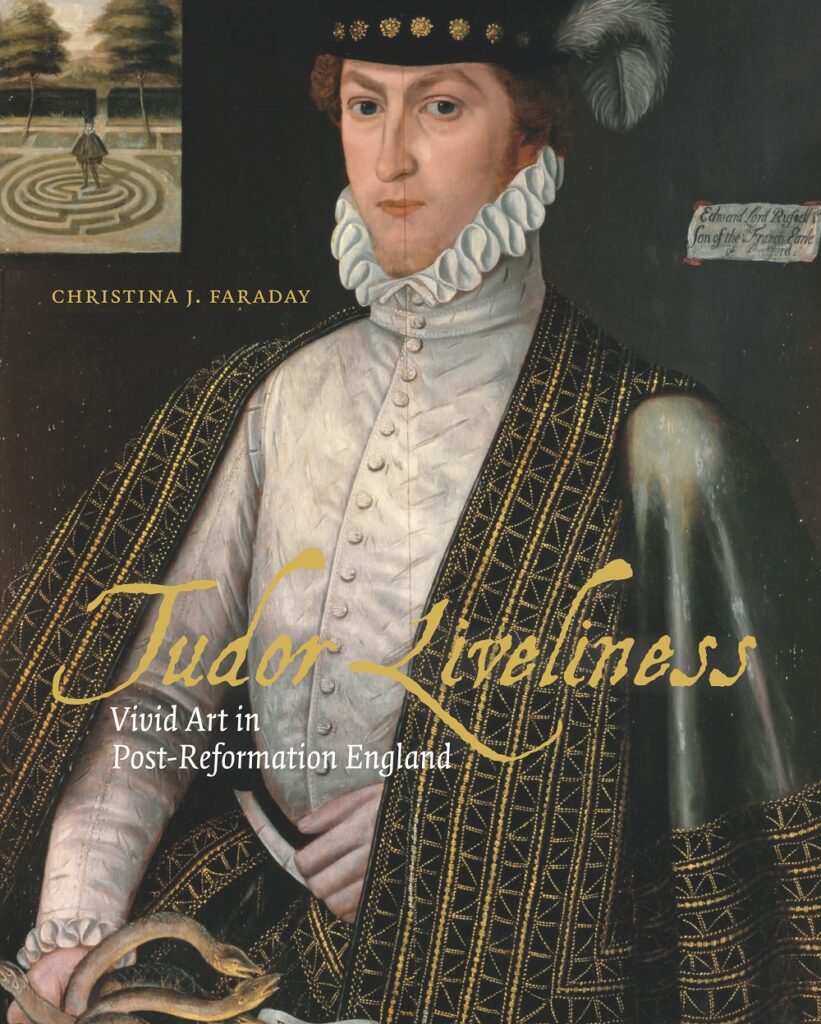

After BA and MPhil degrees in History of Art and Architecture at St John’s, I stayed for a PhD focusing on the problem of ‘realism’ in Tudor art: Tudor paintings often look quite stiff and artificial to us, but at the time people often described them as ‘lively’, meaning vivid and realistic. Through my research I discovered that Tudor ideas about vividness in art were based less on visual illusion and more on what constituted vividness in texts. School and university curricula included classes in rhetoric, where students were trained in the art of persuasion; vivid description was an important tool for persuading and delighting an audience. Guidelines for creating vividness – to make someone feel that they were present at events described, or to feel that they knew the person being lauded in a speech – entered the culture more widely, and Tudor artists seem to have absorbed them too. In narrative scenes they often represent Biblical figures in contemporary dress, emphasising the relevance of holy narratives for contemporary viewers. In portraits they find ways to allude to the sitter’s heritage and achievements through symbolism, mottos, costume and settings.

Researching the Tudor period as a student at St John’s gave me a new appreciation for the sixteenth-century buildings and artworks of the College. St John’s was founded in 1511 by the will of Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII, the founder of the Tudor dynasty. The buildings of First and Second Court are largely sixteenth-century in date, and the Hall, Chapel and Master’s Lodge are adorned with paintings and sculpture from the period I was studying. I even discovered a previously unrecorded engraving by Thomas Gemini, the man who brought copperplate engraving to England, in the Old Library – after a particularly rich dessert in the Buttery left me reluctant to make the trek to the University Library Rare Books Room.

Alongside my PhD I was lucky enough to work part-time as a curatorial intern at the National Portrait Gallery in London on the exhibition ‘Elizabethan Treasures: Miniatures by Hilliard and Oliver’. The experience opened my eyes to the wonders of this intricate art form, but also gave me an insight into the incredible amount of work that goes into an exhibition. Seeing how a show comes together over several years, from the outlining and planning stages to the final installation of the objects in the carefully designed cases, has forever changed the way I look at museum exhibitions.

Currently I am a Research Fellow at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge – just 100m down the road from St John’s! – and still researching Tudor and Jacobean art. My book, based on my PhD, came out last year as Tudor Liveliness: Vivid Art in Post-Reformation England, and since then I have been working on two new projects: an introduction to Tudor art for a general audience, and a book about objects from around the globe that found their way to England in the sixteenth century. I’ve also started to think about more creative ways to promote Tudor art history. In 2023 I organised a seminar series for the Paul Mellon Centre in London, called Tudors Now!, which brought together artists, curators and historians to think about the relevance of Tudor art now. I also recently published an article in the journal Burlington Contemporary about three contemporary artists who take inspiration from Tudor visual culture.

In 2023 I was honoured to be appointed as a Trustee of The Walpole Society, a century-old association dedicated to promoting the study of British art history. This is an exciting time for the Society, which has several new ventures in the works. In 2024 it took over the organisation of the William M. B. Berger Prize, a prestigious award for excellence in British art history. To promote the prize to wider audiences we’ve started a podcast called British Art Matters. As host, I interview the shortlisted authors, discussing their books and exploring the incredible creativity and dedication that goes into their research and writing. The first two episodes were launched in the spring, with Dr Johnny Yarker, Chair of the Berger Prize Judges, and Tim Clayton, author of the 2023 prize-winning book James Gillray: A Revolution in Satire; six more episodes will follow in the autumn when the shortlist is announced. I’m very excited to interview so many scholars working at the cutting edge of the field of British art history, and to broaden my own knowledge of the subject while I’m at it!

Alongside my own research, one of the most rewarding parts of my job is teaching. I teach undergraduates in the History of Art Department and History Faculty, and I’m also a Tutor for the Cambridge Institute for Continuing Education at Madingley Hall, where I co-direct the MSt in History of Art and Visual Culture. Teaching undergraduates one day and lifelong learners the next brings different challenges. Undergraduates love their subject, but they are also looking to develop skills that can help them in any one of a number of careers; we have to think broadly about how our classes can develop them as individuals and future leaders in a range of fields. At Madingley, students are often well-established in their chosen career paths and come to our courses because they want to immerse themselves in a particular subject. Here the focus is often about giving them a more academic angle on material that they often already know a lot about.

Studying art often leaves me with a hankering to make some myself. I’m particularly drawn to the so-called ‘decorative arts’, especially embroidery and ceramics. One day I’d love to learn how to weave. As an art historian it can be hard to let go of the ‘meaning’ of works and the weight of historical reference, so half of any artistic training for me is about learning to abandon myself to the process of making and to think with my hands instead of my head. This is definitely still a work in progress! More usually I find a creative outlet through writing. For the same reason I love art history – the connection it can provide with people from the past – I am a huge fan of ghost stories, and occasionally write them myself. A few years ago I wrote a ghost story inspired by a seventeenth-century legend about a St John’s student who sold his soul to the devil for better exam results – something I hope my own students never resort to!

Christina will be sharing her ghost story set in St John’s at the Spooky Stories virtual event on 28 October. Booking for this will open to alumni shortly.