Dr Giulia Biffi (2010) studied for a PhD in Oncology at St John’s College and the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute. After a period of post-doctoral research at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, she returned to Cambridge in 2020 and set up her own laboratory at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute. Giulia’s lab group focuses on identifying more effective cancer treatments for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) patients that are based on the biological mechanisms that drive cancer.

I consider my experience in academia an example of how, as long as you pursue something you are passionate about, you can change your mind along the way. I went to study Biology at university because I wanted to become an ethologist; I had always been (and still am) fascinated by animal behaviour. However, during my first year, my high school Latin professor was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. That diagnosis, and what followed in the lead up to her death, profoundly upset me and I decided to dedicate my life to researching something that could benefit cancer patients.

During my Masters I had the opportunity to come to Cambridge as my college in Pavia, Collegio Ghislieri, had an exchange programme with St John’s. I picked the laboratory of Professor Shankar Balasubramanian (now Sir!) at the Department of Chemistry. He had a project on telomerase, a protein that is involved in the maintenance of telomeres (the end of chromosomes) and is often hyper-activated in cancer cells. I loved my time in Cambridge, both in the lab and outside, and decided to return to both Shankar’s lab and St John’s for my PhD at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute. Several professors at my university were not supportive of my decision to go abroad. One said it would be “scientific suicide”. They obviously had not studied in Cambridge. I did not listen to them.

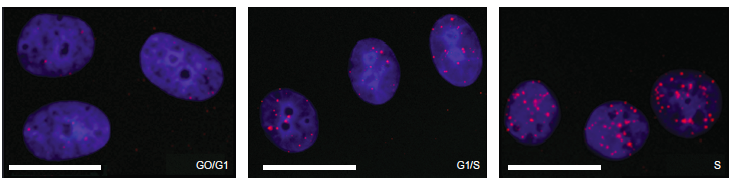

One area of research in Shankar’s lab is the study of G-quadruplexes (also called G4s) which, similar to the double helix discovered by Watson, Crick and Franklin, are secondary structures of DNA. Experimental evidence suggested that they played different roles in biology and, potentially, in cancer. However, when I started my PhD, G-quadruplexes had been observed only in a laboratory setting and their existence in human cells had not yet been demonstrated. Shankar and I felt that, before further studying the potential functions of these structures, we needed evidence that they indeed formed in human cells. I learnt how to do antibody phage display, which enables you to generate highly selective binders to a target of interest. Using this strategy, I developed an antibody that specifically binds to G-quadruplexes. I called it BG4 and used it in immunofluorescence experiments to show that DNA G-quadruplexes do exist in human cells, are in higher number in proliferative cells (such as cancer cells) and can be stabilised by G4-targeting molecules.

At the time I never imagined that BG4 would become such a widely used tool. Now it is applied in a number of different techniques and leveraged to understand the biology of G-quadruplexes in ways that were not possible when I started my PhD.

My first work was published in 2013 – exactly 60 years after the discovery of the double helix. And at least this time a woman was recognised for the discovery! I went on to find that BG4 can also be used for imaging DNA G-quadruplexes in human tissue and RNA G-quadruplexes in human cells. At the time I never imagined that BG4 would become such a widely used tool. Now it is applied in a number of different techniques and leveraged to understand the biology of G-quadruplexes in ways that were not possible when I started my PhD. It is great to see the impact that my PhD work has had and I hope that it will keep enabling new discoveries.

Although I am grateful for my PhD studies and would do it all over again, my real passion has always been more translationally-focused. I thus decided to go to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, in the United States, to pursue a post-doc in Dr David Tuveson’s lab aimed at understanding the biology of pancreatic cancer with the goal of developing new therapeutic strategies. Pancreatic cancer has a really poor prognosis and I felt that any improvement that my research could assist would make a huge difference. Several professors said that I would damage my career by changing field and lose the momentum of being the rising star in the G-quadruplex field. I used to joke that I would have happily been a shooting star instead if it meant going after my passion. I have not regretted it once. Today, I continue my efforts in this field, now in my own lab at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute.

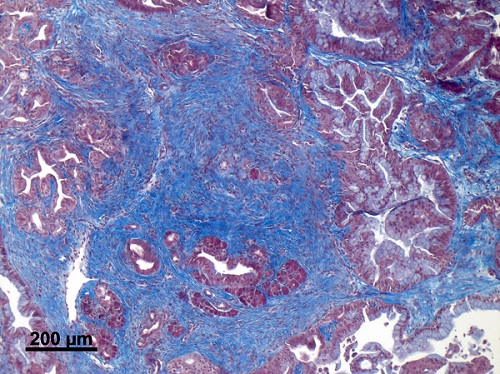

My lab focuses on understanding the biology of non-cancerous cells in pancreatic tumours. It may sound surprising considering that pancreatic cancer is such a deadly disease, but actually pancreatic tumours are mostly composed of these non-cancerous cells, while cancer cells can make up as little as 10% of the tumour mass. These non-cancerous cells help the cancer cells grow, protect them from therapies, and help them spread to other organs. Therapy resistance and metastatic spreading are two of the main reasons why pancreatic cancer is such a deadly disease. In my lab we strive to understand how these non-cancerous cells help the cancer cells and how to stop them from doing so.

Starting my own lab where I did my PhD still feels a bit surreal. When I was a student the dream was to return to Cambridge and become a Fellow (mostly to be able to finally walk on the grass!), but I did not want to become the head of a lab. I thought that I would be much more useful at the bench wearing a lab coat than behind a desk wearing a jacket. However, towards the end of my post-doc I realised that to have a greater impact in cancer research, to do the science I wanted to do the way I wanted to do it, I needed to be my own boss. And it turns out that I really enjoy it because it allows me to train some awesome people, to have a potential impact that alone I would not be able to have, to fight for change in academia, and to still (at least for now) find time to be just a scientist at the bench.

The exponential impact that my trainees and their trainees could have in this field makes me optimistic about a future where pancreatic cancer, and all cancers, will be manageable.

In the next few years, I will keep working to have a positive impact on pancreatic cancer patients and trainees in academia. The exponential impact that my trainees and their trainees could have in this field makes me optimistic about a future where pancreatic cancer, and all cancers, will be manageable. And when that happens, who knows, I may still have time to go and study mountain gorillas.

You can read more about Giulia’s lab group and their work by visiting the group website: https://www.cruk.cam.ac.uk/research-groups/biffi-group