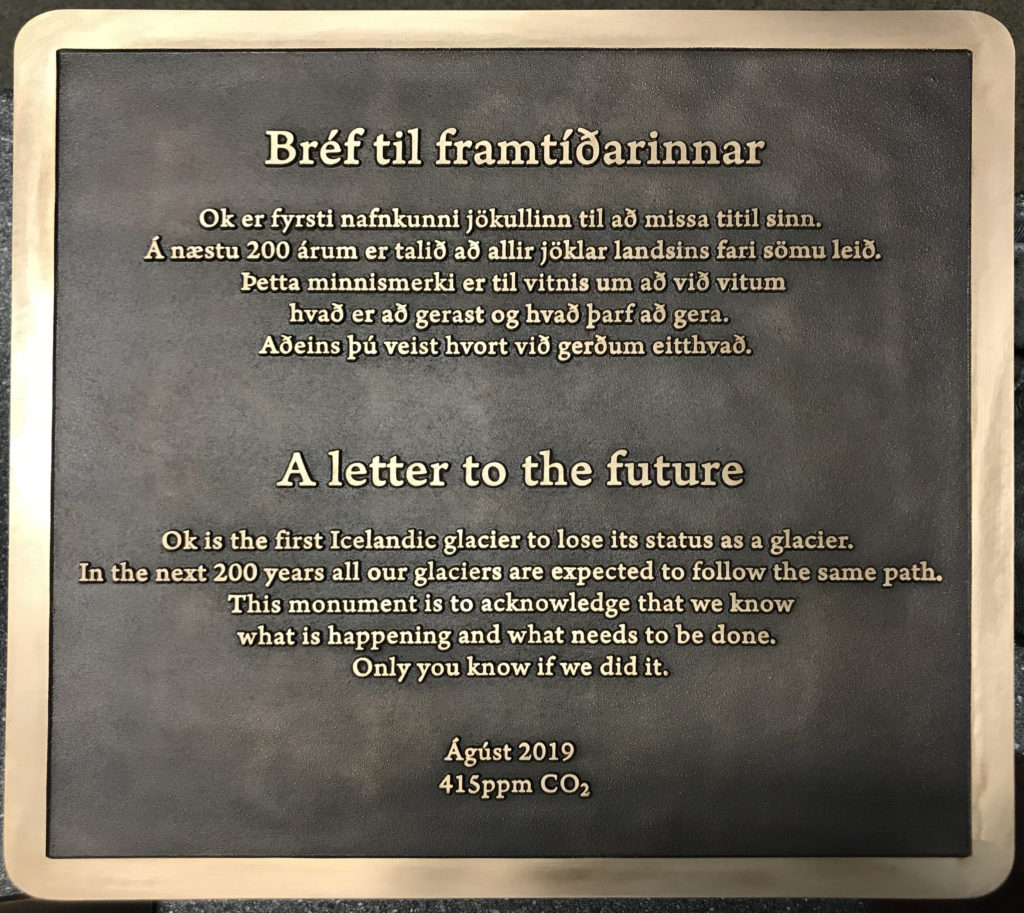

The Ok volcano in Iceland erupted in the Pleistocene era and was capped by the Okjökull glacier until August 2019, when Okjökull was declared the first glacier to have retreated until it no longer existed. This news prompted John Mounsey (1950) to get in touch with an account of the ‘1953 Cambridge Langjökull Expedition’, which was formed to study and map the small icecap before it disappeared.

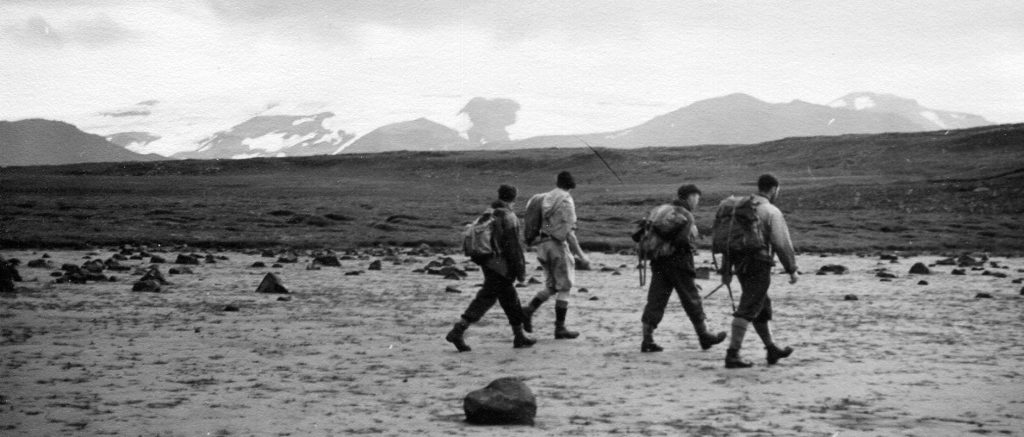

Dick Thompson (1950), another member of the expedition, described the group as ‘good friends from St John’s who were looking to do something original in the world before they got tied to careers’. In addition to Dick and John, whose memories form the basis of this article, the party consisted of Chris Barringer (1950), Cliff Embleton (1949), Jim Conlan (1950), Ian Gardiner (1950) and John Heath (1950).

The party members were all geographers, except for Dick, who was a geologist, and John, who was a biologist. Chris was a geography graduate interested in the extent of the volcanism and the ice coverage of the volcanoes in Iceland, and he was also the instigator and leading organiser of the expedition.

For Cliff, this was the start of a successful research career in glaciology, and he helped Chris with all the arrangements while the others mustered whatever support they could to meet the cost of the expedition. Dick managed to secure the James Wordie travel grant of £25 while John, whose family lived near Kendal, contributed by gathering six weeks’ supply of Kendal Mint Cake!

One member of the party had an uncle who was an Admiral in the British Navy, so the group of seven were made temporary sailors on the Royal Navy Minesweeper HMS Mariner, which took them from Portland to Reykjavik in seven days. They had to swab down the decks and do some paint chipping while the weather was fine, which lasted for the voyage through the Irish Sea. Once they reached the north Atlantic, however, the ship experienced a very severe storm of magnitude ten. ‘Everybody on the whole ship was sick, including the captain’, writes Dick, who remembers swinging wildly in a canvas hammock and not eating for two days.

Eventually, the party arrived in Reykjavik and a truck took them and all their equipment to a farm in Kalmanstunga in a valley immediately below the Ok volcano. The farm had a few small fields where grass grew near streams, but much of the area was grey lava as the volcano had erupted less than 1,000 years ago. After a day’s reconnoitre they set up camp about half a mile from the farm in a sheltered tributary valley by a stream, erecting one large tent for storage, meals and office work, and smaller crawl-in tents for personal equipment and sleeping.

The team had enough food to last them comfortably for the six weeks of their stay, much of it dried, such as ‘pom’ (potato powder), or canned, including pemmican. They also received milk, some greens and occasional salmon and trout from the friendly farmer and his family.

The students were in touch with the outside world by post, which arrived at the farm once a week on Sundays. The postman set off on his weekly round from Reykjavik on horseback, delivering to outlying communities and spending the nights on farms, and it was by this means that they heard about England winning a test match by eight wickets – the only news their Johnian friend Andrew Long (1950) thought worth reporting.

The geographers’ main task was to survey the ice-cap of Ok, about 10 miles from the base camp, so a subsidiary camp consisting of two Black’s Arctic tents was set up on the edge of the ice-cap, which was a perfect dome with a small crater off-centre. Chris and Cliff surveyed the area using a theodolite (a surveying instrument containing a telescope) to accurately measure angles, and they created field drawings using an A3-sized plane table with a spirit level. They were assisted by the others who recorded the observed values.

The weather during their stay, from 8 August until 11 September, was very changeable, as had been expected. The aurora was visible three or four times, and on one night in particular the whole sky was lit up in quivering streaks and bands – usually white but for a few minutes now and again brilliantly green, red and purple – dancing across the sky

‘I poked my head and shoulders outside the tent to watch’, John recalls. ‘I was quite hypothermic by the time the show was over.’

All surveying was frequently hampered by mist, so posts were driven in at the limits of visibility and back-sights taken. Line measurements at different angles across the ice were made, and the group later found that straight lines taken in this way were surprisingly accurate. Compasses were useless because some of the local rocks were magnetic, so sightings were taken on clearly identifiable landmarks – and, in addition, a number of cairns set up close at hand were given a coat of yellow paint to make them more clearly visible. A number of pits were also dug to investigate the soil profile in an attempt to reveal its history.

Dick spent most of his time carrying out a geological survey of the area, walking miles on his own and wading across many shallow rivers, which were very cold as the water had come from melting glaciers and snow fields. Thinking back on it now, he admits that if anything had happened to him, he might have been rather hard to find! He found it a great help to plot the geology, which comprised a succession of lava and ash outpourings, on a topographic map.

There were ‘the most excellent examples’ of lava textures, including ropy lava, and a very wide and shallow anastomosed stream flowing over a layer of recently generated glacial gravel, where a flow of lava down the main valley about 1,000 years ago had created an almost flat valley floor.

John was responsible for surveying the flora, for which he didn’t feel particularly well equipped, since the botany course for his Cambridge degree did not include a thorough knowledge of the subject.

Luckily John had his mother’s copy of Bentham and Hooker’s British Flora, which included the great majority of the Icelandic species. Once John had identified and collected pressed samples of most of the local plants, he constructed a meter square frame (a quadrat) in wire to try to characterise the main communities, discovering that the soils ranged from basic over the basalt to strongly acidic in the peaty areas.

The group completed their surveying work after six weeks and travelled ‘cattle class’ on the regular Icelandic ferry ship the Gullfoss, where the accommodation was pipe-and-canvas bunks on a deck partitioned by canvas curtains. After disembarking at Leith in Scotland, everybody in the party scattered to various destinations and most never met again.

Unfortunately the measurements and notes recorded during the trip were subsequently lost, but when John looks back he is struck by how far times have come: ‘All the laborious measurements made by our party could now be made from a chair in front of a computer screen showing the latest satellite images!’

Were you aware of climate change during the expedition?

I can’t remember whether we knew for sure that the Ok mini-glacier was shrinking, but we were all well aware that glaciers all over Europe and Scandinavia were retreating. In 1955 Chris Barringer and I helped to dig a tunnel through the icefall at the head of a Norwegian glacier where the shrinking was all too obvious.

John

In 1953 it wasn’t appreciated that Iceland was a surface example of sea floor spreading – it was not until 1962 that Hess published his paper on the ‘History of Oceans’ and provided proof of continental drift – so this didn’t form part of our survey. As a geologist, my focus at the time was to see the unique fresh exposures of lava recently erupted under ice.

Dick

What do you think of the current climate crisis?

Understanding the world has come a long way since 1953. Continental drift is now widely accepted and there are survey markers to record this: the results show that East Iceland is slowly moving away from West Iceland.

Dick

I feel quite glad that I shall not be around much longer to see the tremendous geopolitical problems which seem likely to ensue, and I am sorry for my grandchildren. That said, my neighbour Mike Berners-Lee is a professor at Lancaster University and the author of There is no Planet B, and he is hesitantly optimistic that we might be able to avoid the worst climate changes. Fingers crossed!

John

Written by

Hannah is the Alumni Relations Officer (Publications) at St John’s. Overseer of the alumni blog and Editor of Johnian magazine and The Eagle, she commissions, writes and edits articles from and for Johnians. Previously, she worked for Clare College and the Cambridge Schools Classics Project, and she holds an MA in Classics from the University of Cambridge (Trinity Hall).