On Saturday 26 September, alumni came together for Johnian Society Day — organised by Johnians for Johnians to celebrate their shared connection with the College. Unlike in previous years, the wetness of the weather in Cambridge was irrelevant (the event being held entirely online), and the enjoyment of the experience was in no way dampened.

Professor Tim Whitmarsh, in one of his final appearances in his role as Vice-Master, opened the event with a pithy welcome message, in which he pointed out that virtual events have become the new norm and quipped that in lieu of College food and drink, attendees would receive food for thought. He gave a quick update on admissions, explaining that St John’s is welcoming record numbers of undergraduates this year, including from state schools and under-privileged backgrounds. He ended the introduction with a glowing review of the College’s incoming Master Heather Hancock: ‘not just razor-sharp in intelligence, good with people and a great organiser, but also a genuinely lovely person’.

Chair of the Johnian Society Mark Wells (1981) thanked Tim for being a fantastic Vice-Master during such a tough year. He then introduced the panel discussion ‘From Farm to Fork — Making Food Sustainable’, which consisted of back-to-back ten-minute presentations, followed by questions from the audience.

The first panellist was Dr Victoria Avery (1988), Keeper of Applied Arts at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. She has co-curated critically acclaimed exhibitions, including Feast & Fast: The Art of Food in Europe, 1500–1800. Victoria’s presentation summarised the cultural context and history of food production.

Slides included visuals from her Feast & Fast exhibition, including an impressive blown-up print of an edible food arch from Naples, represented in a book from 1629.

Many of the concerns we have about food today — foodbanks, genetically modified food and eating disorders — had resonance and close parallels in the early modern period.

As exploration opened up new trade partners, new exciting foods were distributed and dynasties competed for global trade. This led to new recipes and a broadening of experiences, but also to exploitation.

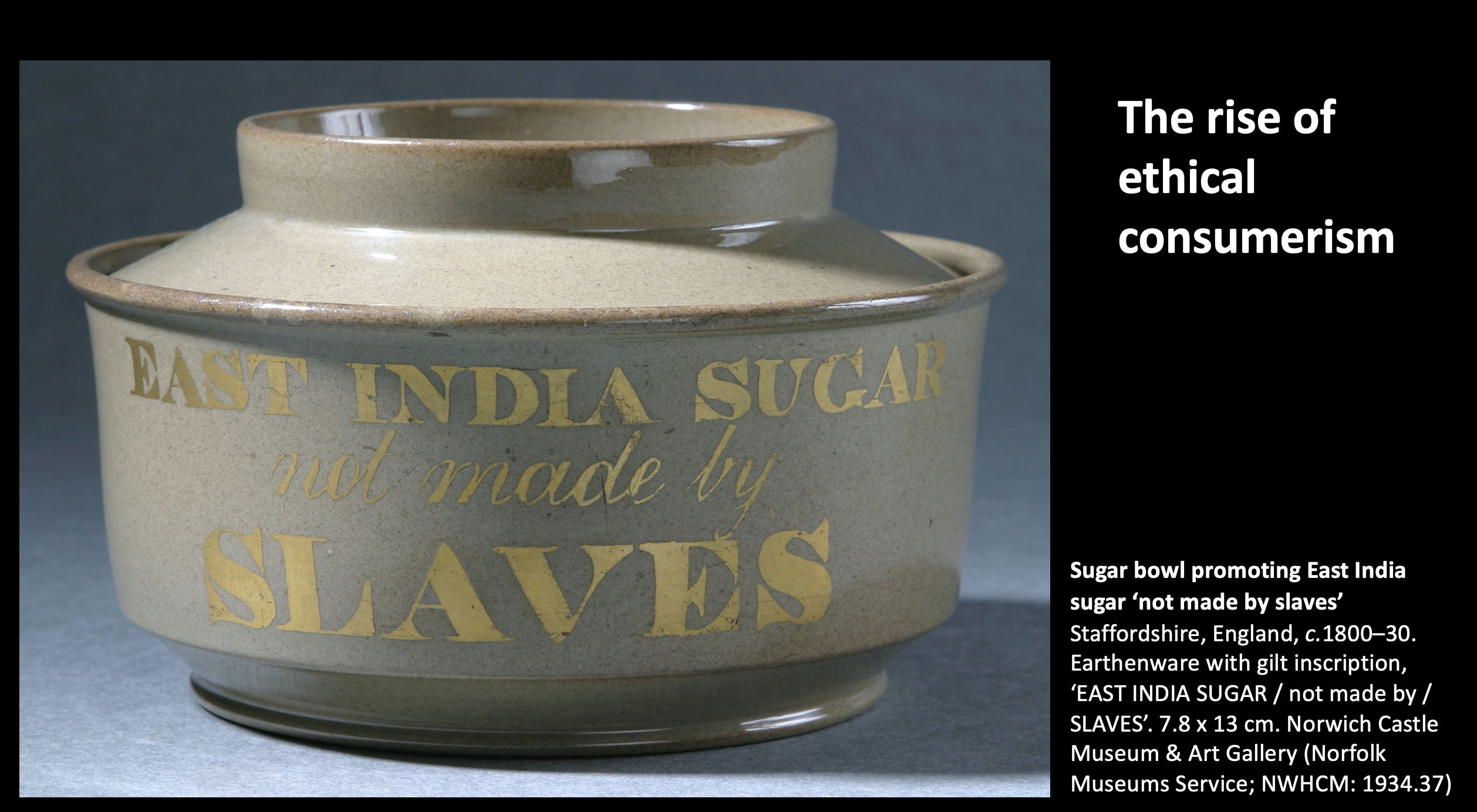

Over time, sugar went from being a wealthy, elite substance to a poor-man’s luxury. It became a generally available commodity as slaves were put to work in appalling conditions on sugar plants in Jamaica and the Caribbean. By the end of the 18th century, the public were becoming conscious consumers, wanting to know how their food was produced. Victoria shared an example of the marketing slogan painted onto a sugar bowl c 1800–1830: EAST INDIA SUGAR not made by SLAVES. In this case the sugar would have been made by indentured workers instead, which was not much better. Still, the item reveals that ethical consumerism was already having an effect on the market by the early 19th century.

As an example of how attitudes towards food and animals rights have changed in the past couple of centuries, Vicky presented an illustration of hunters capturing cranes — a practice that resulted in the term ‘hoodwinking’.

Hunters dug holes and put paper bags inside with seeds at the bottom and sticky bird lime around the edges. While the cranes ate the seeds, the bags stuck around their necks and the hunters were able to catch them while they flailed blindly. The book this illustration was taken from explained hunting practices in a context celebrating man’s ingenuity — but we would read the image rather differently now as a blatant infringement on animal rights.

Emily Norton (1997), a farmer from Norfolk, Co-founder of Nortons Dairy and Head of Rural Research at Savills, gave the next presentation. Emily began with the history of farming, summarising the First Agricultural Revolution (8000BC in the Fertile Crescent; the transition from hunting and gathering to settled agriculture and taming species), the Second Agricultural Revolution (1700–1880 in the East Anglian heartlands; the introduction of new crop rotations and selective breeding of livestock) and the Third Agricultural Revolution (1940–2005, known as the Green Revolution; the introduction of chemistry).

Emily explained that we are currently in the Fourth Agricultural Revolution (2005–), which is based upon the digitalisation of agriculture and represented by the separation of food from soil-based systems. World population and wheat yield are steadily increasing, but biodiversity and other indicators of environmental wellbeing are steadily declining. How do we address this problem? Emily suggested returning to ‘Agriculture 2.1’, returning to methods from the Second Agricultural Revolution but enhanced through our greater understanding of technology.

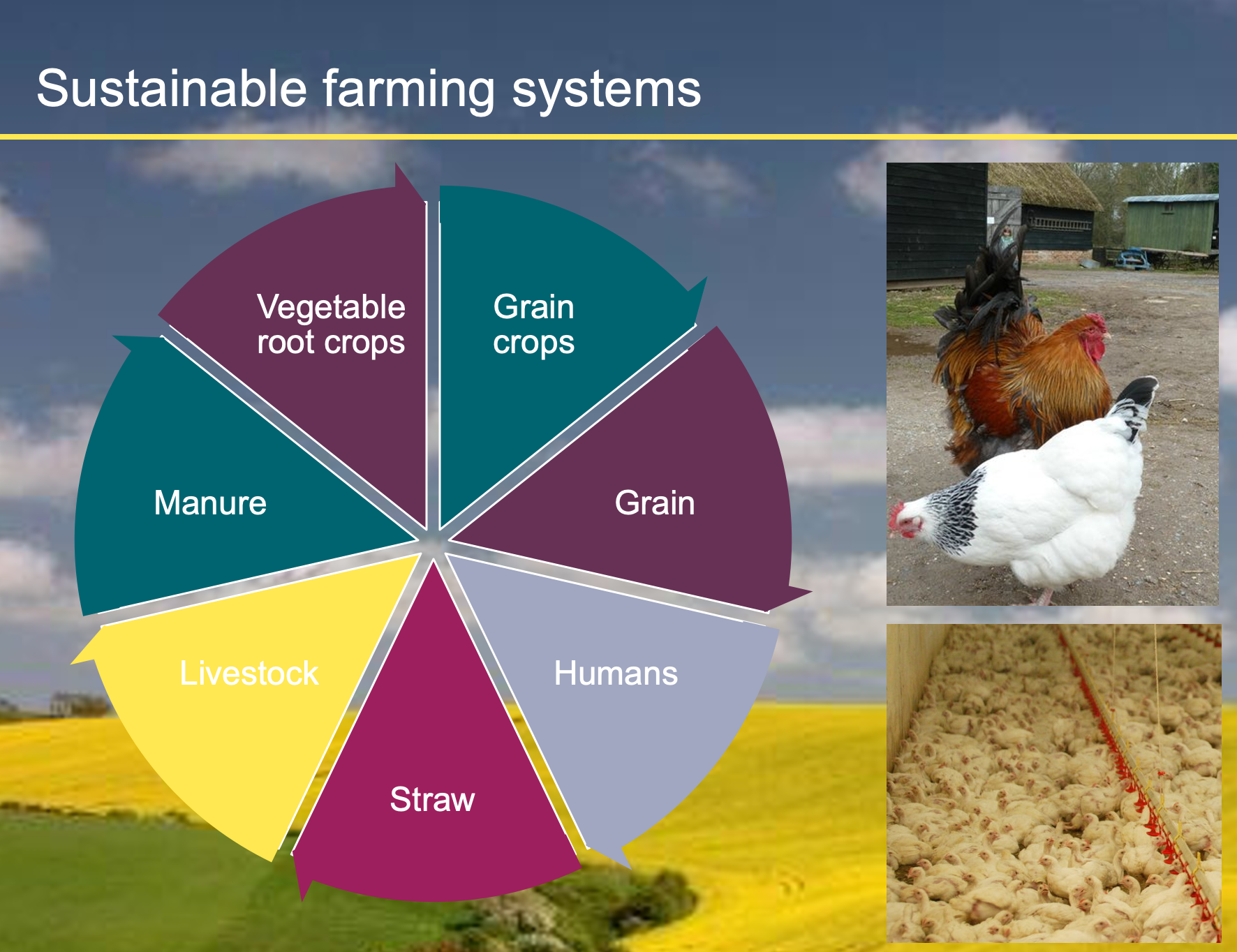

The Second Agricultural Revolution created balanced, sustainable farming systems (rather than pushing crops to their genetical limit) while producing surplus to free up more workers for other roles in society. Often people assume that food production is balanced because farming systems are constrained by the inherent limits of soil and nature, but external economic market forces have skewed the balance and resulted in, for example, the intensive chicken farming we have now in order to produce cheap protein.

Real disruption is on the horizon for mass manufactured food. Emily predicted that if these pressures on price and efficiency continue to be the dominant forces in our food production system and in our economy, then ‘I can’t believe it’s not chicken’ replacement protein sources (and equivalent) are inevitable. The inefficiency of producing chicken is to put a beak and feathers on it, and the market will no doubt embrace a way of doing that without wastage and co-products that need to be exported.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) was introduced post-war to promote an excess of food over need to ensure that food could be presented to consumers at reasonable prices. The goals of CAP were very clear and have been reasonably successful, but the question now is how do we introduce environmental goals and protection into the system? As far as farmers are concerned, Emily suggested thinking about system changes that are within their own control, adopting a very balanced, high-quality regenerative and circular agricultural system, and accepting that trade can balance the rest.

John Vincent (1990), CEO and Co-founder of LEON Restaurants then shared his thoughts on the impact of food production on the environment. He joked that he had always been last-minute when it came to deadlines, leading to many essay crises at University. The world now seems to be in a similar position when it comes to sustainability and the environment, except that this is a real crisis that affects billions.

John referenced a speech that Michael Gove gave at Brighton College, in which he quoted from Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises. The character Mike is asked how he went bankrupt, and he answers: ‘Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.’ This echoes how the world is falling into a sustainability crisis where our food production processes have resulted in a dramatic decrease in the microbial diversity of our planet’s soil. Moreover, 75% of all water pollution and 20–30% of greenhouse gasses result from the way we produce food.

The food systems that were created after World War II to solve hunger are now paving the road for our extinction. However, laying the responsibility solely on the government is futile, especially since there is such a high turnover of DEFRA Ministers and government staff. John argued that one of the roles of the government is to create a ‘safe playground’ for others to step into and offer help, and he was cheered that many more people are waking up to the reality and severity of the global situation.

A great step companies can take is to adopt Natural Capital Accounting, which essentially documents externalities (factors outside the direct balance sheet of a company) to prove that a company is actually creating value. Leon aims to match the nutritional needs of the individual with the sustainability needs of the planet, and John is focused on making as many aspects as possible of the chain nature-positive. This includes embracing more plant-based foods and moving further away from meat; biodiverse farming; and adopting construction practices that enhance wildlife in the company’s buildings.

‘We don’t have cheap food. We just have wrongly accounted for food.’

John has set up a Council for Sustainable Business, and as Chair he believes that the next big measure should be a carbon tax that is spent on replanting the rainforest. Consumers should also educate themselves on the hidden external costs, such as the cost of health and the cost to the environment, that are often not factored into the price of food.

The three speakers then took questions from the audience, including how farmers might be encouraged to take up Natural Capital Accounting. John answered that this is a two-part process: companies need to be inspired to adopt it, and then they need to have the practical help and direction to do so. In his role as Chair of the Council for Sustainable Business, John has brought together different groups who are in favour of Natural Capital Accounting to encourage united conversation and collaboration between them.

At 3pm guests were invited to make drinks and take a short break, during which a contemporary acapella set from The Gentlemen of St John’s was played. The group had recorded the songs in Chapel earlier in the week especially for the Johnian Society Day. The song choices included ‘Teenage Dirtbag’ by Wheatus and ‘With a Little Help from My Friends’ by The Beatles. They finished with ‘Blue Moon’ by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, dedicating the song to Chris and Mary Dobson.

The afternoon pub quiz consisted of two parts, with the first round centred on St John’s and the second on Cambridge more broadly. Questions, written by Peter Scott (2002), ranged from the unabbreviated name of the SBR (Answer: the Samuel Butler Room) to the last Johnian to be Prime Minister, after holding the office on more than one occasion in the 19th century (Answer: Henry John Temple, Lord Viscount Palmerston).

Following the quiz, Mark Wells matched the five-minute record for the AGM, aided by well-coordinated and unanimous hand-raising from members. The meeting confirmed the re-election of Graham Spooner (1971)and Annamarie Phelps (1984)in their respective roles as President and Vice-President of the Johnian Society for another year. Three new members were also appointed to the committee: Stuart Mayes (1957), Wilfried Genest (2010) and Michael Gun-Why (2002).

The day ended with guests raising glasses, many of which were filled with cocktails prepared from the recipes shared by Bill Brogan. Mark Wells toasted the College — ‘Close to our hearts, if not geographically today’ — and Tim Whitmarsh responded ‘Long live the Johnian Society’.

PS if you are eyeing the beautiful photography of St John’s College that guests were using as backgrounds, you can download them for your Zoom account below.

Punts at the River Cam: download picture here.

Top of College Chapel: download picture here.

Written by

Hannah is the Alumni Relations Officer (Publications) at St John’s. Overseer of the alumni blog and Editor of Johnian magazine and The Eagle, she commissions, writes and edits articles from and for Johnians. Previously, she worked for Clare College and the Cambridge Schools Classics Project, and she holds an MA in Classics from the University of Cambridge (Trinity Hall).