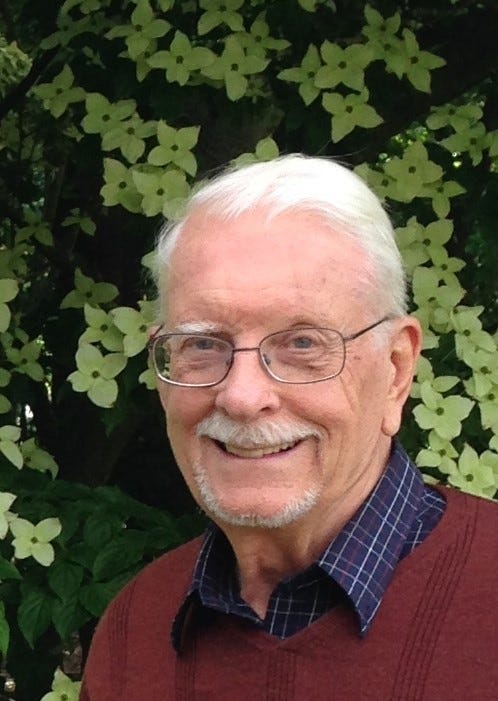

At the end of his final year at St John’s, John Hoyte (1953) accepted a travel scholarship to research how Hannibal crossed the Alps. An account of this adventure appeared in The Eagle 2020, published and mailed in October 2020. Years after the initial research trip, the idea resurfaced — with a twist. In this article, John sets the scene for his second Alpine adventure, this time with an elephant in tow!

In the summer of 1956, my friends and I took advantage of a travel scholarship offered at St John’s to set out on the ‘Cambridge Hannibal Expedition’, in which we trekked and rated several potential routes through the Alps to contribute to the debate over which way Hannibal had crossed into Italy from Spain. It concluded with evidence in favour of the Col de Clapier pass and a three-column article was printed in the London Times titled ‘Cambridge Carthaginians’.

By September 1958, a little over two years after our initial Cambridge Hannibal Expedition, none of us were thinking of the Hannibal debate. I was a graduate apprentice at Joseph Lucas Inc., an engine manufacturer in Birmingham, and I was staying at the downtown YMCA. Joe, a friend also staying there, was interested in planning a climb in the Alps. One evening, I sat down with him and shared the slides and scrapbook of our trip. Joe whimsically asked, ‘Why don’t you take an elephant?’

I laughed as I recounted all the reasons it would be impossible: no money; no elephant; no experience; no reason to justify it; no possibility; no way. But the question lodged in my mind, and I could not get to sleep that night. I began to imagine the possibilities. What if I were able to get an elephant? I started to think in terms of we instead of I, for Richard, my best friend at Cambridge, would have to be involved if anything as challenging as this were to work. We shared a similar crazy imagination, and had already climbed Hannibal’s possible passes together.

The next day was another workday. My evening was free, so I got out my portable typewriter and put together three letters to the British consuls in the closest major cities to the Col de Clapier. My request was simple: Would they happen to know anyone who might have an elephant available for a British expedition over the Alps following Hannibal’s route? Of course, I couldn’t write as a poor engineering apprentice from the Midland of England. With sheer audacity, I wrote representing a new entity: the British Alpine Hannibal Expedition.

I could not get to sleep that night. I began to imagine the possibilities.

What if I were able to get an elephant?

A week later, I was waiting in line for buffet supper at the YMCA, in possession of a long envelope from Turin that I had just picked up from the mail room. The line was moving slowly, so there was time to open it, revealing the Royal Coat of Arms and the letterhead ‘British Consulate, Turin’. It read:

Sir: Unusual as your request may be – well, unusual, I should perhaps say, for a Consulate – I am happy to inform you that I have been able to secure the offer of an elephant for your projected crossing of the Alps next summer.

My eyes grew wide as I read and reread the letter. It went on to say that on the very day my letter had arrived, La Stampa, the local newspaper, mentioned a particularly energetic young elephant at the Turin Zoo. Thereupon, Mr Bateman, the consul general, called the zoo, reaching Arduino Terni, the managing director. ‘Would you have an elephant available’, Bateman asked him, ‘for a British expedition over the Alps following Hannibal?’ Not only was the response positive, but Signor Terni also offered to provide the elephant free of charge. He may have thought of this as good publicity, but the sheer generosity of the act overwhelmed me.

Imagining Jumbo, our elephant, striding along with our group as we crossed the Alps was difficult for me, but there it was. I had an elephant for a new expedition. The greatest hurdle of all, finances, seemed magically to have disappeared, since the addition of Jumbo could be expected to generate sponsorships and other income from newspaper and magazine publicity.

Just the next day, the reality of the offer began to sink in. Then came the doubts. An expedition would attract international interest. Was I capable of organising and running an expedition of this magnitude? I had never led an expedition of any size, let alone one with this potential. The Cambridge climb had been an exploration by four like-minded friends. None of us had been the leader. Now the team, whoever would be in it, would need real leadership.

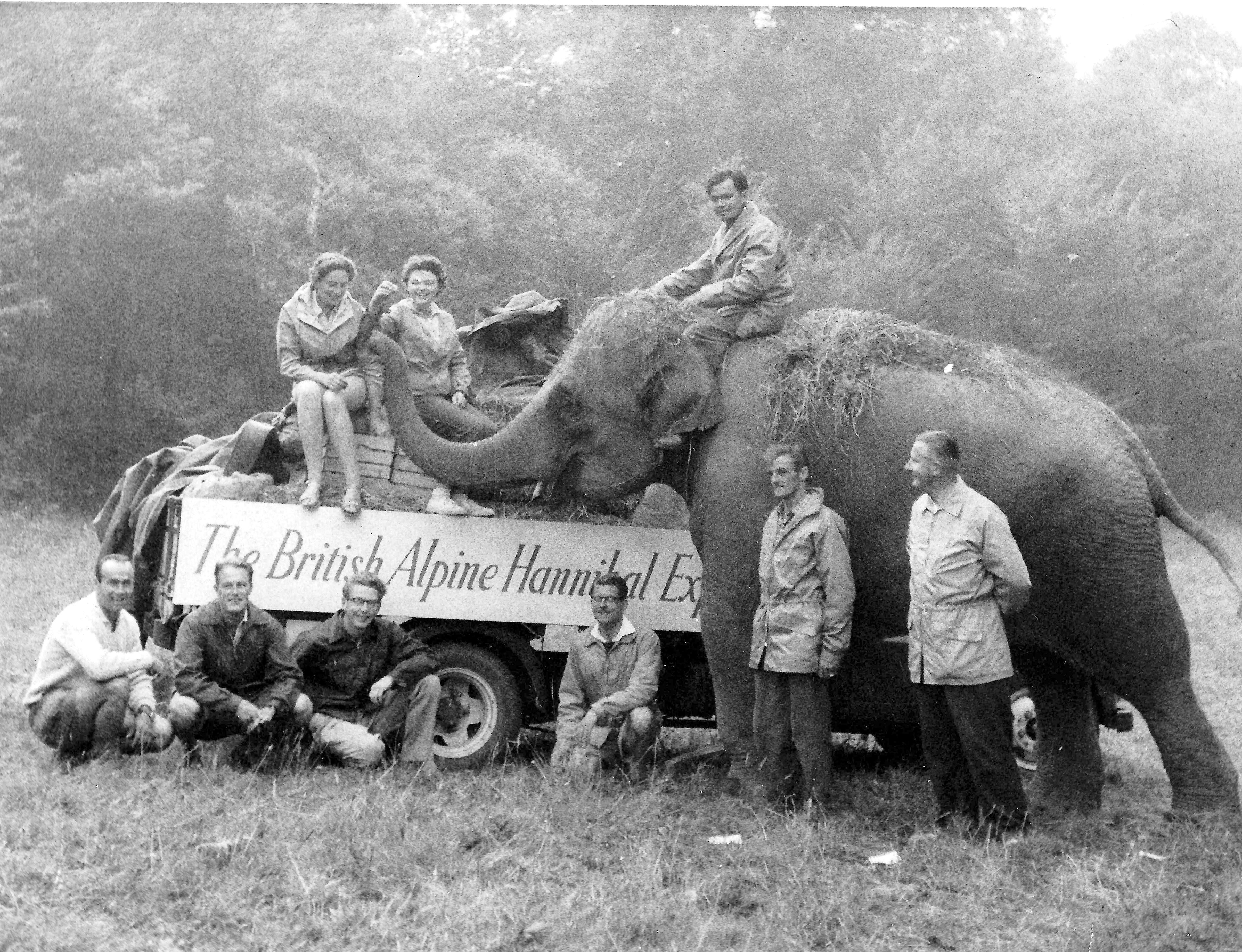

Richard, in far-off Kenya, wrote that he would be available. As soon as he returned to England, Richard and I sat down and drew up a list of the needs and responsibilities. By the middle of June 1959, our team had taken shape:

John Hoyte: leader and publicity officer

Richard Jolly: secretary and leader of the daily advance guard

Professor John Hickman: veterinarian

Cynthia Pilkington: treasurer, linguist, and cook

Jimmy Song: photographer

Michael Hetherington: quartermaster and classicist

Clare Garden-Smith: cook and assistant quartermaster

Baldi:our truck driver, provided by the generosity of Signor Terni at the zoo

Ernesto Gobold: mahout

The daily plan itself was simple: When Hannibal marched, we would march. When he rested, we would rest. When he fought the Alpine tribes … we would rest!

That always brought a laugh when I lectured in later years. Then I would tell of the many unique problems our expedition faced: no Alpine warrior tribes, but extensive worldwide publicity.

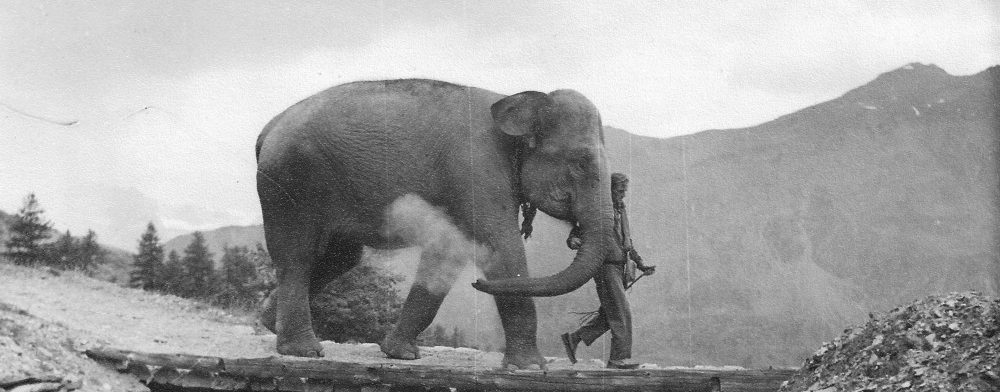

At Pontcharra, we commenced the real journey ‘in Hannibal’s tracks’.

July 20, 1959

Good morning, Hannibal. This is the first day of our journey and quest to rediscover your route over the Alps. We seem to have enough information – particularly from Polybius – to know your passage. We have been able to procure a young elephant for the journey and hope to learn something of your difficulties and triumphs in our re-enactment of your crossing. We believe we are the first to take an elephant along your route since you did, so, in a sense, we will be travelling with you.

I have so many questions. How did you feed the elephants? We’re guessing that you did not make them carry anything except platforms on their backs to conserve their strength. What was it like for you personally to command a large army? How strict were you with high standards for your officers and men? How did you manage mercenaries? I would love to know more about your sense of humour.

Such were the thoughts running through my mind as we set out. For weeks, I had wondered how it would be to walk with an elephant in the Alps. Now we were retracing Hannibal’s route and letting our imaginations run wild as we imagined his thirty-seven elephants, their smell, their trumpeting, and the calls of their mahouts…

Read more about John’s Alpine trip with Jumbo the elephant in his memoir The Persistence of Light, a copy of which can be found in the St John’s College Library alongside his first book, Trunk Road for Hannibal. Both memoirs can be purchased online.